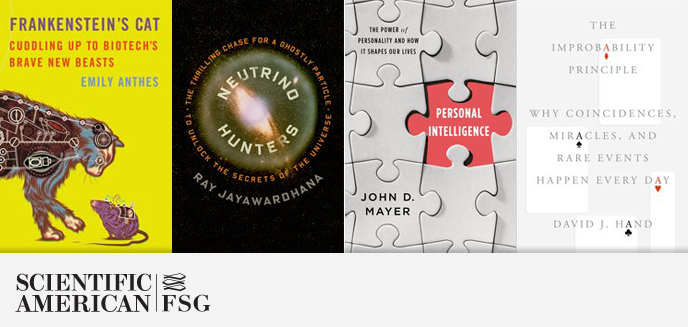

Scientific American/ Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Our Scientific American imprint authors and editors offer up the best science books they read this year.

EMILY ANTHES, author of Frankenstein’s Cat:

Wild Ones, by Jon Mooallem

Wild Ones, by Jon Mooallem

An exploration of the ways that humans threaten the world’s wildlife–and the long, strange lengths to which we’ll go to save it. Surreal, dark, funny, and hopeful, often, somehow, simultaneously.

Salt Sugar Fat, by Michael Moss

An exhaustively researched book that goes deep inside the food industry to show how corporations manipulate manufactured foods to keep consumers snacking. It’s no surprise that the industry puts profits above health, of course, but the book is compulsively readable; deftly weaves together science, history, and commerce; and includes startling admissions from former industry bigwigs. You’ll never look at Cheez-Its the same way again.

The Good Nurse, by Charles Graeber

A riveting true-crime tale of a murderous nurse and the hospitals that did far too little to stop him.

Toms River, by Dan Fagin

A masterpiece of environmental reporting that illustrates how little real life resembles Erin Brockovich. It turns out that it’s notoriously difficult to find definitive cancer clusters, let alone link them to toxic exposures–and harder still to hold polluting companies accountable, even when their environmental misdeeds are obvious.

RAY JAYAWARDHANA, author of Neutrino Hunters:

Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air, by Richard Holmes

Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air, by Richard Holmes

Not a science book per se, but a dazzling account of the often enchanting and sometimes fatal adventures of the pioneering balloonists. I read this wonderful chronicle while on a tall ship in the Arctic with a group of writers and artists, not far from where Salomon Andrée’s ill-fated balloon flight to the North Pole took off.

DAVID J. HAND, author of the forthcoming book The Improbability Principle:

The Theoretical Minimum: What You Need to Know to Start Doing Physics, by Leonard Susskind and George Hrabovsky

The Theoretical Minimum: What You Need to Know to Start Doing Physics, by Leonard Susskind and George Hrabovsky

This is a book for “people who once wanted to study physics, but life got in the way. They had had all sorts of careers but never forgot their one-time infatuation with the laws of the universe. Now, after a career or two, they wanted to get back into it, at least at a casual level.” And it’s wonderful.

The Elements of Eloquence: How to Turn the Perfect English Phrase, by Mark Forsyth

This hugely entertaining book lays bare the secrets of memorable phrases and beautiful English. I laughed out loud, and have already sent copies to friends.

JOHN D. MAYER, author of the forthcoming book Personal Intelligence:

Neutrino Hunters: The Thrilling Chase for a Ghostly Particle to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe, by Ray Jayawardhana

It’s just been released and I haven’t read it yet (except a very engaging excerpt), but I’ve put it on my “to read” list based on what I’ve seen so far.

Top Brain, Bottom Brain: Surprising Insights into How You Think, by Stephen M. Kosslyn and G. Wayne Miller

Kosslyn is a world-class researcher in cognitive psychology and neuropsychology; Miller, a science journalist and author. Kosslyn and Miller describe a new insight emerging from contemporary brain research: that the upper reaches of the brain’s cerebral hemispheres think differently from their lower portions. Kosslyn and Miller argue that people express different thinking styles depending on which part of their brains they favor. Top-of-the-brain thinkers are more abstract pattern-perceivers and planners; bottom-brain thinkers deeply process individual instances; and some people use both (or neither). The style that works best for a person will depend on the individual’s context; Kosslyn & Miller’s bottom line is that it helps to know one’s own personal style (they provide a diagnostic test), and it often makes sense to work in teams with people who vary in the parts of the brain they use. Throughout the book, they bolster their argument with evidence from key studies, meta-analyses of brain functioning, and a new scale of cognitive style. The writing is lively and accessible, and I was excited about the idea of using insights from brain science to identify new dimensions of our character.

Kosslyn is a world-class researcher in cognitive psychology and neuropsychology; Miller, a science journalist and author. Kosslyn and Miller describe a new insight emerging from contemporary brain research: that the upper reaches of the brain’s cerebral hemispheres think differently from their lower portions. Kosslyn and Miller argue that people express different thinking styles depending on which part of their brains they favor. Top-of-the-brain thinkers are more abstract pattern-perceivers and planners; bottom-brain thinkers deeply process individual instances; and some people use both (or neither). The style that works best for a person will depend on the individual’s context; Kosslyn & Miller’s bottom line is that it helps to know one’s own personal style (they provide a diagnostic test), and it often makes sense to work in teams with people who vary in the parts of the brain they use. Throughout the book, they bolster their argument with evidence from key studies, meta-analyses of brain functioning, and a new scale of cognitive style. The writing is lively and accessible, and I was excited about the idea of using insights from brain science to identify new dimensions of our character.

PAUL RAEBURN, author of the forthcoming book Do Fathers Matter?

The Cancer Chronicles: Unlocking Medicine’s Deepest Mystery, by George Johnson

One of the best books I read this year begins this way: “As I crossed a dry, lonesome stretch of the Dinosaur Diamond Prehistoric Highway, I tried to picture what Western Colorado–a wilderness of sage-covered mesas and rocky canyons–looked like 150 million years ago, in Late Jurassic Time…” The book goes on to talk about the supercontinent of Laurasia, and the graveyards of Stegosaurus, Brachiosaurus, and others. If the title hadn’t given it away, you’d be surprised to discover that this is a book about cancer, and its author, George Johnson, is beginning at the beginning–with fossils containing some of the earliest known evidence of cancer. The book is called The Cancer Chronicles, and it’s a polite, almost gentle book about that most brutal of diseases. This story, which begins with fossils, ends in a place you might not expect. No spoilers here; I suggest that you pick up a copy.

JENNIFER OUELLETTE, co-editor of The Best Science Writing Online 2012:

Jennifer wrote about her thirteen favorite physics books of 2013 on her “Cocktail Party Physics” blog on the Scientific American site. You can read about all of her selections here. Here is a sample of a few of her favorites:

Jennifer wrote about her thirteen favorite physics books of 2013 on her “Cocktail Party Physics” blog on the Scientific American site. You can read about all of her selections here. Here is a sample of a few of her favorites:

Newton’s Football: The Science Behind America’s Game, by Allen St. John and Ainissa Ramirez

Exploring the physics behind our most popular sports represents an entire genre of popular science writing, and this is one of the best recent books along those lines. I loved it so much, I provided a blurb: “What do you get when you pair a journalist and bestselling author with a materials scientist turned science ‘evangelist,’ and have them collaborate on a book about football? With any luck, you get Newton’s Football, a breezily informative and fun exploration of the science behind this popular pastime, from Vince Lombardi’s use of game theory to helmet design and why woodpeckers don’t get concussions.” Perfect for the science-loving football fan on your shopping list.

Five Billion Years of Solitude: The Search for Life Among the Stars, by Lee Billings

This book has been getting a lot of much-deserved critical praise; it is top-notch science journalism. The ongoing hunt for exoplanets is a white-hot topic, and Billings does a fantastic job not just summarizing the science behind the hundreds of exoplanets discovered thus far, but also in tracing “the triumphs, tragedies, and betrayals of the extraordinary men and women seeking life among the stars.”

LAIRD GALLAGHER, Editorial Assistant at Farrar, Straus and Giroux:

On Looking: Eleven Walks with Expert Eyes, by Alexandra Horowitz

As a self-styled flaneur and something of an intellectual dilettante, I found Alexandra Horowitz’s book an ideal fit for my 2013. I moved to New York City this summer and spent long afternoons wandering the avenues and cross-streets. Horowitz’s book offered new ways of taking in the urban landscape, through the eyes of entomologists, typographers, geologists and even young children. Together, these walks build into a modest philosophical meditation on the relationship between perception and knowledge—the way our world gives itself through lenses shaped by experience and expertise.

The Outer Limits of Reason: What Science, Mathematics, and Logic Cannot Tell Us, by Noson Yanofsky

Who doesn’t love a good paradox? I’ve always been fascinated by what science cannot explain, where logic falls flat and where mathematics bends back on itself. I’m still making my way through Noson Yanofsky’s comprehensive inquiry into science’s insufficiencies, but I’m captivated by what I’ve read so far. With almost no equations or abstract figures, Yanofsky describes what might be true but cannot be proven, the limits and contradictions between relativity theory and quantum mechanics, the complications surrounding notions of the infinite, and the logical inadequacies of everyday language. Much like Jim Holt’s Why Does the World Exist?, this book hits a sweet spot square between hard science and philosophy.

AMANDA MOON, Senior Editor at Scientific American / Farrar, Straus and Giroux:

It was another incredible year in the world of science books. This year, I’m sharing, in no particular order, the ten that stayed with me the most (apart from the titles we’ve published here!) and that I keep recommending to anyone who will listen. I hope you find them as enjoyable, compelling, riveting, informative, and surprising as I have.

Toms River: A Story of Science and Salvation, by Dan Fagin

The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light, by Paul Bogard

The Best American Infographics 2013, edited by Gareth Cook

The Smartest Kids in the World: And How They Got That Way, by Amanda Ripley

Who Owns the Future? , by Jaron Lanier

Wild Ones: A Sometimes Dismaying, Weirdly Reassuring Story About Looking at People Looking at Animals in America, by Jon Mooallem

Animal Earth: The Amazing Diversity of Living Forms, by Ross Piper

The Kids’ Outdoor Adventure Book: 448 Great Things to Do in Nature Before You Grow Up, by Stacy Tornio, Ken Keffer, and Rachel Riordan

Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas, by Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker

Big Data, by Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Kenneth Cukier