Seamus Heaney’s death last week left a rift in our lives, and in poetry, that won’t easily be mended. A Nobel Laureate, a devoted husband, a sharp translator, a beloved friend, and the big-hearted leader of the “Government of the Tongue,” Seamus was a poet of conscience; his close-friend and fellow poet Paul Muldoon said, “He was the only poet I can think of who was recognized worldwide as having moral as well as literary authority.” Poetry was a vocation that he dedicated his life to, something he believed had “the power to persuade that vulnerable part of our consciousness of its rightness in spite of the evidence of wrongness all around it, the power to remind us that we are hunters and gatherers of values, that our very solitudes and distresses are creditable, in so far as they too are an earnest of our veritable human being.” Uncannily attuned to the voices of the world around him, his poems made both the personal and collective subconscious realms concrete in language.

In this time of sorrow for his family, friends, and the literary community, we would like to celebrate his remarkable life and work. Seamus Heaney was our Wordsworth, our Keats, our Hopkins, our Yeats. To commemorate this remarkable artist, we asked some of his friends and fellow poets to share a memory or a reflection on his work. We are grateful to Paul Muldoon, Henri Cole, Robert Pinsky, Frank Bidart, Maureen N. McLane, Michael Hofmann, Tracy K Smith, Rowan Ricardo Phillips, C. K. Williams, August Kleinzahler, Jay Parini, Adam Zagajewski, Charles Wright, Spencer Reece, James Lasdun, Rosanna Warren and Paul Elie for their contributions.

We will continue to add to our tribute in the coming weeks as more people come to us with their remembrances.

—Christopher Richards, FSG

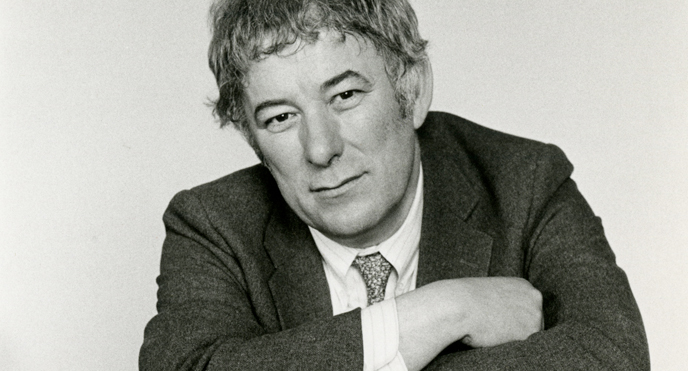

Seamus’s later, official photographs have an impassive dignity—as if they are yet another responsibility he is shouldering uncomplainingly, as he did so many others. They are stoic, tolerant, modestly monumental, but without the buoyant good humor and gusto everyone who encountered him got a real taste of.

The outpouring of emotion on his death—not just in his native Ireland, where his sudden passing was received as a national tragedy, but in America too, where it was above-the-fold front page news—had to do not simply with the greatness of his poetry, but even more, I think, with the utterly natural, manly way he inhabited the role of the bard—with the unassuming humility of one who nevertheless knew he owned it. The new pope, Francis, shares some of Seamus’s inspiring down-to-earth authority. He was a common man who had had to accept that he was also best in the class, teacher’s pet, his mother’s favorite, and was consequently ever mindful of potential backlash from the toughs who might have expected him to be one of them. In his youthful pictures he looks like a footballer, with his squarish bovine head—except for the haunted eyes, the bowlike lips and satyr’s curls. He could have been the heart-of-gold curate all the women in the parish fell in love with. Instead, he took his gift for Latin in a very different direction and became “Incertus,” delving with a pen rather than a shovel.

His early poems had the rough decision of absolute newness—new speaker, new matter, new address. “Digging” is the classic locus, but there are many, many others across a prodigious career in which he continually rose to the challenge of “Keeping Going.” His translations are marvels, imbued with the directed force that made him the poet of his time and place. He became surer and gentler as he went along, and his later work sometimes had the humane reasonableness of the smiling public man—though, luckily for him, he was far too Christian to be Yeats’s heir; he was only himself, always. He seemed lately to have found affinities in the intimist work of the Italian Giovanni Pascoli. Little has been said in these days about his brilliance as a critic, but he was a great teacher and interpreter. His perspective was universal and he spoke deeply to poets who could not begin to approach or maybe even hear his musicality, and to readers of all stripes, everywhere.

Seamus was a truly good man who may have worked too hard to preserve his inborn simplicity—too many books signed, too many generous letters praising the efforts of others, too many unnecessary (but to whom?) demands on his time. Seamus Famous enjoyed celebrity and celebrities, but he knew how to shame the envy out of the close-knit, often fractious community in which he was always head boy, using his inclusive laugh and natural fellow-feeling to turn the competition into colleagues and friends, the brothers and sisters in the art they aspired to be and were at their best, which was whenever he was around.

His visits to New York after he gave up teaching at Harvard following the Nobel Prize were more infrequent, but the tradition of oysters and martinis with the other FSG tenors Joseph Brodsky and Derek Walcott and company at Roger’s table at the Union Square Cafe continued long after Joseph and then Roger went missing. Seamus and Joseph; Seamus and Derek; Seamus and Ted Hughes; Seamus and Czesław Miłosz; Seamus and his honorary sister Helen Vendler; Seamus and Paul Muldoon (a familial bond with an Oedipal inflection); Seamus and John Scanlon, the rakish Irish-American publicist with whom he shared in a bit of bad-boy fun; Seamus on the road with Karl Miller and Andy O’Hagan; Seamus and the ever-expanding cadre of younger poets who looked to him for encouragement and inspiration: just a few imaginary snapshots from the enormous album of his close connections.

In recent years (though not in 2013) he and his wife Marie often spent much of January in St. Lucia with Derek and his wife Sigrid, where they participated in Nobel Week, honoring the country’s laureates Derek and Sir Arthur Lewis, and were first among equals in the crowd who plied a catamaran down the coast for Derek’s birthday lunch at Ladera. Seamus’s Derry skin was not made for the Caribbean sun, but he was always at the heart of the party: eating local delicacies on the beach, drinking and enjoying the music with a group of younger writers who always seemed to turn up wherever he and Derek were, and basking indulgently in their unintrusive love. Their last time together was a joint appearance at the AWP conference in Boston this past March. The night before, at a gathering of Boston poets, Seamus raised an eloquent glass to friendship and Marie spontaneously chimed in with a haunting ballad.

Seamus Heaney gave poetry a good name. Few have demonstrated its essential presence in the world more convincingly. We were lucky to have known him, as we will continue to in his unforgettable work.

Seamus Heaney and Derek Walcott, Boston, March 2, 2013, taken by Marie Heaney

When I arrived yesterday morning at Belfast International Airport I offered the border official my US Passport. He asked me about what I did in the US. I was a teacher. I taught poetry. He looked at me and said, “You must be devastated this morning, then.”

Something about the frankness of this response, its unvarnished aspect, reminded me of a phone call I made to the Heaney household one night years ago. Maybe thirty years, now. The phone was answered by one of the boys. Michael, I’m pretty sure. He was a teenager at the time. Having known him since he was a kid I was glad to have a chance to have a chat and hear what he was up to. After a while, Michael ventured, “I suppose you’ll want to speak to head-the-ball?” Not being a parent at the time, I was a little taken aback by the familiarity, perhaps even the over-familiarity, of this nomenclature. Even if Michael didn’t call Seamus “head-the-ball” to his face (which I’m pretty sure he didn’t), I realize now that it was a very telling moment. It was a moment that suggested a wonderfully relaxed attitude between father and teenage son, one I now see as highly difficult to establish and maintain.

The Seamus Heaney who was renowned the world over was never a man who took himself too seriously, certainly not with his family and friends. That was all of us, of course. He had, after all, an unparalleled ability to make each of us feel connected not only to him but to one another. We’ve all spent many years thinking about his poetry. We’ll all spend many more years thinking about it. It’s the person rather than the poet I’m focusing on today. The person who did everything con brio, “with vigor.” This was, after all, the Seamus Heaney who repurposed Yeats’s description of a bronze chariot in his poem “Who Goes With Fergus?” and referred to his BMW as a “brazen car.” However the Seamus Heaney we’re here to celebrate today might be described, “brazen” is hardly a word that comes to mind. Anything that smacks of ostentation would be quite inappropriate. As would anything that smacks of meanness of spirit. A word that might come to mind is “bounteous.” And, while I’m in the realm of the B’s, maybe even “bouncy.”

This last may seem a bit strange but I have a distinct memory of playing football with Seamus, Michael and Christopher somewhere in or around Glanmore. When I say “football,” I need to be clear, particularly when this might well have been back in an era when soccer was perceived as a foreign game. Let’s put it like this. This was not a game in which Seamus’s talent for heading the ball was ever called on. It was Gaelic football, and I have to tell you that I speak as someone who’s been shoulder-charged by Seamus Heaney. He bounced me off like snow off a plough. He rebuffed me. Benignly, though. “Benign” is another word that comes to mind.

Actually, “benign” is somewhat inadequate. “Big-hearted” is coming closer. On the subject of the heart, when Seamus was fitted with a monitored electronic device a few years ago he took an almost unseemly delight in announcing “Blessed are the pacemakers.” Seamus’s big-hearted celebrity attracted other celebrities, of course. Movers and shakers always attract movers and shakers. Was it a young Michael (or a young Christopher, perhaps?), who was introduced to a couple of dinner guests and inquired of each of them in turn, “What is it you’re famous for?” To return to Seamus’s capacity to act con brio, I don’t think I’ve ever seen another human being, with the possible exception of Usain Bolt, move with such speed and accuracy as did Seamus when he heard the then toddler Catherine-Ann cry out in distress after falling in the yard. He positively sprinted, swept her up in his arms, brought her to a safe place.

It was Seamus Heaney’s unparalleled capacity to sweep all of us up in his arms that we’re honoring today. Though Seamus helped all of us develop our imaginative powers we may still only imperfectly imagine what Marie is going through. She above all recognizes that other great attribute of Seamus Heaney. I’m thinking of his beauty. Today we mourn with Marie and the children, as well as the extended families, the nation, the wide world. We remember the beauty of Seamus Heaney – as a bard and, today, in his being.

*Paul Muldoon’s text was delivered as a eulogy at Seamus Heaney’s funeral in Dublin on September 2, 2013.

It is no accident that Seamus Heaney’s collection of selected poems is titled “Opened Ground,” since writing poems for this most remarkable farm boy was a kind of digging: “Between my finger and my thumb/ The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.”

And it’s no accident that this selection of the best poems from three decades begins with the word “between,” for Heaney was a poet of the in-between (as his friend Helen Vendler has observed), writing from a zone somewhere between north and south, between Catholic and Protestant, between Ireland, England, and America, between formal and free verse, between public and private, between realism and allegory, and between plain speech and loading “every rift with ore,” while also balancing the gravitas of his subject matter with the frolic and grace of poetic language. As Heaney said, “The point is to fly under or out and beyond those radar systems.”

A poet must remain, no matter the cost, “open,” experiencing, if possible, both sides of any debate—whether it be with one’s government, or with one’s beloved, or with one’s self. And so it is no surprise that Heaney’s “Opened Ground” ends with that word—“open”—for this is the necessary condition of any authentic, great poet. But “How to be socially responsible and creatively free, while being true to the negative evidence of history?” This is the question Heaney was always struggling to answer while making poems of aesthetic beauty and converting the roughness of our human experiences into complex harmonies.

But what a sad day this is, for Heaney has escaped from us and he belongs to literature now. His title, “Opened Ground,” resonates with a special sorrow.

As Marianne Moore said: “The forces which result in poetry are irrepressible emotion, joy, grief, desperation, triumph.” Heaney’s subjects were: What is loyalty? What is exile? What is righteousness? What is love? And how do we govern our emotions? These are themes that preoccupy all of us. And though he lived in a divided Ireland with tanks, posted soldiers, and other degradations, I never heard him claim representative status as a victim.

I think of Heaney as an ethical poet, because he was very much alert to the transformational properties of poetry to console, educate, and improve. He believed writing could change things, as in the episode from the New Testament, where Jesus writes in the sand and diverts a crowd from stoning a woman who has been caught committing adultery. It’s Jesus’s writing on the ground with his finger that diverts the angry mob, and as Heaney said, “it takes the eyes away from the obsession of the moment.” Poetry, he believed, could achieve this, too.

As a man, Heaney was a poet of immense dignity. I say this as his former colleague and as a poet from a younger generation, who was searching for ways of being in the literary world. When I saw him not long after he received the Nobel Prize, he absolutely refused to use “the ‘N’ word,” as he called it, when telling the story of how he’d been in Greece on a road trip with his wife, Marie, when news of his—“N” word—was announced. Word didn’t reach him until he phoned home routinely and his son exclaimed: “I’m so proud of you, Dad!” When Heaney was a student poet at Queen’s University, his pseudonym was Incertus—Latin for “uncertain.” And as far as I could tell, the Nobel Prize only deepened his humility.

To me, Heaney’s title, “Opened Ground,” also suggests that something is being exhumed and examined, as if from a grave. It reveals a man refusing to be sentimental as he digs around and extracts truths from his soul and from the world. Whenever I read a Heaney poem, I am reminded of Wordsworth’s “The Prelude,” where he looks out over the side of the boat at still water, solacing himself, and sees the gleam of his own image mixing up with pebbles, roots, rocks, and sky. Time, history, thought, and self all merge in an alluring way—exactly as they do in Heaney’s best poems, where, after he has been digging, there is germination and a flowering.

*Henri Cole’s tribute previously appeared on The New Yorker’s “Page-Turner” blog.

Seamus in his study in 2009, photograph by Henri Cole

LABOR DAY

The streets are bare

but for an old woman

and the ornamental dog

she loves and walks

by a Marimekko’d quartet

eating spaghetti Bolognese

al fresco as the day

and awning allow.

No peat or bog here

but asphalt, glass,

steel and cement

and this too was your element—

nothing human alien

and nothing of cloud

or clod or rush

of wind across this pond

hedged round by towers

we’ve babylon’d

up from an island.

You knew all

about islands.

In the park the families

toss Frisbees in a late sun.

An ice cream day,

gay, ghastly holiday,

but the signal’s clear

and the flown signaler.

You are nowhere

but in all the air.

Labor is blossoming

or dancing where

you set the darkness echoing.

Like the apple

made substantial

in Cezanne’s paint your throated

fruit and bivalves

split along seams

only you could sound out.

With your passport green

between turf-face and demesne

you wrong-footed them all

with your sure surprising step.

Your vowelling embrace

of the mossy places,

the consonantal thrusting

through blood- and wander-

and just plain lust—

a villanelle

for a Harvard occasion,

a refusal to toast a queen

you nonetheless thought

did her job

all things considered

quite well—

You are elusive and central,

Sophocles and the mead-hall

heart-threaded into an English

the English could not but hail

along with everyone called

by the tongue of the tongue—

as if in one earthbound orthogonal

windswept man all

the chaos of the clan

were stayed and cleared—

an opening a throat the sun

could not but shine from.

When considering the lives of writers, an unpleasant truth emerges: Many of them, including some great ones, were mean or petty or worse. I’ve often thought to myself, Thank god for Chekhov, who demonstrated that a great writer could be generous, large-hearted, unselfish, tolerant.

The same goes for Seamus Heaney: His understanding of other people, individually and in groups and in nations, made him a master of occasions and a supreme teller of jokes and stories. The same quality makes him a great poet. Thank god for him, too.

*A longer version of Robert Pinsky’s tribute previously appeared in Slate.

I have a photograph, a snapshot, I cherish: Seamus, Adam Zagajewski, Paul Muldoon and I are standing on a sidewalk in New York, all of us smiling at the camera. The reason we’re all smiling as broadly as we are is because Woody Allen had just stepped out of a limousine beside us, and though we’d tried to hail him, to say hello, or compliment him, or whatever one thinks one will enact in the presence of such vastly public entities, Allen had rushed by us into a doorway without a glance in our direction.

We all stood, perhaps a bit taken aback, and then, “My goodness,” Seamus said, “he was scuttling, wasn’t he? Just scuttling right along.” And it was true, that was the precise and now only word to describe Allen, his posture, his velocity, and the odd, barely suppressed desperation of his gait. He had indeed scuttled out of our ken, and we were all standing there delighted, not by Allen, of course, but by Seamus’s having plucked that word out of both the air, and—we surely, poets all, heard the echo—of “J. Alfred Prufrock,” and its famous scuttling ragged claws.

Seamus was hardly a comic poet, but remembering this incident, I realize that there was a similarity to the way he’d chosen that particular word, and the way he made choices for his writing. In both his poetry and prose, there’s always a kind of gentle pressure, in the images, the narratives, the ideas, the words. Nothing for the sake of shock, no abrupt gestures towards the glamorous; just that constant but never insistent ratcheting of language and thought one turn beyond what normally would be expected.

I don’t have to add, because it’s been said a thousand times this week, that he was a gentle man, in all senses of the word. In person he was curious, attentive, generous, good humored. In the identity he created for himself as poet, he was all of that, and much more: a consciousness and conscience as formidable as any our time has known.

After Seamus Heaney’s reading for the Academy of American Poets at the Pierpont Morgan Library, 1996. (from left: Bill Wadsworth, Seamus Heaney, Paul Muldoon, Charles Pierce, Matt Brogan, Jonathan Galassi, Marie Heaney, and Derek Walcott)

Seamus Heaney had the uncanny ability to translate the being of the world into language. His words seemed to short-circuit the ego constructions, ego combats that make up so much of our speech. He invented a language that carried the weight of our physical beings, our existence as creatures on a physical earth. His language, at times autobiographical, modest or even seemingly tossed-off, was beautifully impersonal—instantly recognizable not only as his own, but as “the music of what happens.” It made inescapable not only the graces and pleasures of the earth, but (far rarer among poets) tragedy.

The moral insight and balance that his writing possesses he possessed as a person. It has become a commonplace to say this about him; weirdly, it’s true. Generosity and tact. The ability to see the necessities and accomplishment of writing very different from his own. His presence at any gathering of writers calmed the scene, as if briefly we were not a gaggle of competing egos but made up a genuine community.

You can find something in Heaney’s poems that you can find no where else. Part of the world is returned to you there that is returned no where else. The news, two days ago, was that Seamus “died.” People will never stop wanting to read Seamus Heaney.

I somehow saw him in five decades. From the 70s—when I, then an undergraduate and agnostic, and I’ll be honest, even a little antagonistic (I disliked word-play at the time), heard him reading from Field Work—to (my luck) earlier this year, in May, in Dublin. The usual unpredictable run of poetry occasions, gratefully seized where I was concerned: the coincidences in the orbits of an increasingly astral body and a satellite that didn’t really fit in anywhere. What turned me was a reading Seamus gave in Rotterdam in 1984 or 1985 when I noticed I had shivered like a malaria patient through his six poems. I was a little shocked at how familiar they were to me. They had somehow inscribed themselves. I adopted him, wrote about him, was proud, absurdly, to share an initial with him (“Alphabets”!), and bear the same name as his son. One of the few times he made a public fuss about anything (remember the kerfuffle about Eminem?), when he reminded the British his passport was green, that made an obscure bond between us as well: I can’t claim to be Irish, but my passport was also green, then. The oddest occasion (because it was one of mine, or not even that) was probably in London in 1995 when I was at the German Embassy collecting a prize on behalf of my late father, and Seamus appeared, grinning broadly, in someone’s tow. It was the sort of unscripted, improvised situation he manifestly relished. There followed a convivial evening under the sky, a long table on a cobbled mews outside a pub in Belgravia. Many long tables furnish forth a life. I want to say: comportment to juniors matters. Going around with him in Cambridge, Mass., in 1988, when he and Marie had very kindly taken me in for a couple of days, I had the sense that he had turned the place into his village. (And then I thought how everywhere to him or with him probably was like that, or got to be like that. He was a Midas of a better sort.) People came popping out of shops and running out of houses to greet him. It might have been a crane shot in a happy-ending film. He absolved it all, as I think he always did, with attentiveness and grace. No one ever seemed to go away from him empty-handed or empty-hearted. Surely there was no obligation on a person of his gifts to be so generous? How could he, who gave so much and was needed so much, still have anything left? There wasn’t and he did. He graced our little scene—and other, bigger, more important scenes—with his kindness, his decency, and—say it—his intellect, his reading, his thoughtfulness, his tough-mindedness, his exactingness. He didn’t ration himself or stint himself. He was an ornament and an adventure, both. Seeing him straightened you out, reminded you of what mattered. It was good to be on hugging terms with Seamus: he was “like a solid wedge of oak,” as he quotes Virginia Woolf on Yeats in Stepping Stones, the inestimable Dennis O’Driscoll’s book of interviews. He was much more in my thoughts—and many people’s thoughts—than he can have known. It’s our retaliation, our gratitude. I signed off the last time, “intermittently but always very much yours.” No more intermittence now, no more periodicity, no more abeyance.

Seamus Heaney had been my teacher two years in a row at Harvard. After I graduated, and returned home to California to be with my mother as she battled end-stage cancer, his voice as a teacher and a poet served as a kind of beacon of insight and hope in my life.

Alone in my room, by my window overlooking the rooftops and the low hills that were wet and green in the distance, reading poems to myself became a kind of ritual. The slim volumes I’d brought home with me from college offered me a sense of continuity between the life I’d begun to lead on my own, and the life I’d been drawn back into upon returning home. Every time I set foot in my room, it was as though I were chasing the handful of poets I’d come to know while I was away—chasing because I didn’t want to let them get away, didn’t want them to swerve out of my grasp. (I was certain they’d want to escape, given how little I knew how to say, and how little there was there to command their attention.) Those winter afternoons—upstairs with the pack of my most necessary poets: Seamus Heaney, Elizabeth Bishop, Philip Larkin, Yusef Komunyakaa, and William Matthews stand out in my memory as particularly vital to me at the time—were teaching me something about what it felt like to try and regard the totality of something I’d only ever known in part. A life, they told me, is made of what happens and what is lost. Looking back, we learn to name those things, to see and understand them. We hold them for a minute, looking first with innocent, untrained eyes. But if we hang there for a while longer, we can step into a different kind of gaze, one capable of seeing what is absent, longed for, what has been willed away or simply forgotten.

There’s a sonnet sequence called “Clearances” in Heaney’s book The Haw Lantern that I found myself returning to again and again. It was an elegy for his mother. I had a visceral love of one particular sonnet about the two of them peeling potatoes while the other family members are away at Sunday mass. I suppose it reminded me of all the days when I was my mother’s tiny satellite, accompanying her everywhere, safe and happy at her side. But the poem that resonated most mysteriously for me was the sonnet that closes the sequence:

I thought of walking round and round a space

Utterly empty, utterly a source

Where the decked chestnut tree had lost its place

In our front hedge above the wallflowers.

The white chips jumped and jumped and skited high.

I heard the hatchet’s differentiated

Accurate cut, the crack, the sigh

And collapse of what luxuriated

Through the shocked tips and wreckage of it all.

Deep-planted and long gone, my coeval

Chestnut from a jam jar in a hole,

Its heft and hush become a bright nowhere,

A soul ramifying and forever

Silent, beyond silence listened for.

What did it mean to be both empty and a source? Was there something I housed, or might one day house? Something the loss would enable me to give? Or was it her loss that was the source of something? Would something worth having eventually spring from it?

I thought sometimes of how I’d chosen to look up in the first moments after her death. I had made a pact with myself that I would, wanting to show her my face, to tell her I believed she was on her way, as she’d assured us she would be. I’d turned my face up to that bright nowhere, wanting to feel what it housed, wanting to show that I knew it housed not just something, but my mother, my source. What hurt so much in these months after her death was exactly what Heaney’s poem knew how to name: that my gaze in those moments had been pointed up toward a place beyond my discerning, a place I’d never hear or reach or know as long as I was myself.

But the poem didn’t just lament that aspect of loss; it created a conundrum of presence and largeness, a realness more real than the absolutes we live by: “A soul ramifying and forever / Silent, beyond silence listened for.” Such language consoled me. And it beckoned me to the page, pushed me to see whether I might be capable of writing truths like that into being, truths that would prove better than the ones that eluded or exhausted me from moment to moment in this new life—even if the only one to read or believe or to need them in the first place would be me.

*A version of this was read by Tracy K Smith at a tribute to Seamus Heaney at the 2013 AWP Conference and appeared on graywolfpress.org.

What, in these brief days since he’s left us, is there left to say? Seamus Heaney has had an effect on my work to such a depth that I am only recalling now as I write this things I am not yet willing to disclose because the poet in me, which is all of me, somewhat distrusts disclosure. So what is there left for me, in particular, to say. Who fed and fled from being the allegory of the Poet, the Irish Poet, the Great Poet, better than Seamus Heaney did. He was fluent in this century, crisp; and now that I’m left to this century without him, what was inevitable now feels terrible. The power and the glory of poetry in our language––its poignancy––has suffered a blow that feels like a coup de grâce, and I reel and feel unwell. Poetry is not dead but poetry has died a little. Seamus Heaney’s greatest poetic gift might have been that he was not outshone by any one, or few, of his poems or by any particular style he chose. In this sense, his name is a synecdoche for great poetry: precision and openness, actuality and myth, the storyteller’s skill seduced by uniquely sonic priorities; a brilliant Platonism in that his work always read like a sublime translation of an ever more sublime source. I always thought of Seamus Heaney more in terms of “I can’t wait to read his next poems” than “Let me sit, again, with this same group of poems,” which I hope is a compliment that arrives to you through the murky curtain of the canon. For now is when there is, of course, the tendency to sum Seamus Heaney up by what may seem his most canonical moments––much time again with “Digging” (the gun) and “Death of a Naturalist” (the flaxdam and frogspawn), among others, in which we perhaps relive that first encounter with, and reckoning of, his trajectory into the rarest of atmospheres. I am no different when it comes to Field Work (a tremendous influence on The Ground), and yet I feel so strongly tied to Human Chain, his last book. How rare to find a poet so far along in his career and his splendor, neither spent nor spoiled but utterly exposed and in that exposure nothing but grandeur to be found. And how rare to find a final poem such as “A Kite for Aibhín” at the end of the human chain, with its triple-ghosting of Pascoli and Dante and rhyme . . . and its summit between childhood and advanced age at the peak of that “one afternoon / All of us there trooped out / Among the briar hedges and stripped thorn . . .”

A KITE FOR AIBHÍN

After “L’Aquilone” by Giovanni Pascoli (1855-1912)

Air from another life and time and place,

Pale blue heavenly air is supporting

A white wing beating high against the breeze,

And yes, it is a kite! As when one afternoon

All of us there trooped out

Among the briar hedges and stripped thorn,

I take my stand again, halt opposite

Anahorish Hill to scan the blue,

Back in that field to launch our long-tailed comet.

And now it hovers, tugs, veers, dives askew,

Lifts itself, goes with the wind until

It rises to loud cheers from us below.

Rises, and my hand is like a spindle

Unspooling, the kite a thin-stemmed flower

Climbing and carrying, carrying farther, higher

The longing in the breast and planted feet

And gazing face and heart of the kite flier

Until string breaks and—separate, elate—

The kite takes off, itself alone, a windfall.

Photograph by Mariana Cook, 2001

I first encountered, and fell for—hard—the first couple of Heaney collections around 1972 or so. This would have been at the University of Victoria’s library where I was attending university and studying with Basil Bunting at the time. These early poems, the spade in the bog poems, remain my favorite Heaney. Not so long after first reading Heaney, maybe 1972 or so, I was back home in New Jersey when I read that Seamus was giving a reading at the Donnell Library in New York.

I crossed the Hudson with some excitement to hear him read. I remember Louis Simpson introduced him. Seamus was a young man then, clearly on a meteoric rise, but quite shy, still slender, and soft-voiced, not the practiced reader he would later become. And he still had a bit of the farm to him, if I recall. It was wonderful, really. He was.

The news on Friday that Seamus Heaney had died brought him warmly to mind. He was, for me, the central poet of the postwar era, and a good friend of more than forty years. One often heard him described as the successor to Yeats, and perhaps in Irish terms that makes sense. But he seemed to me more like the successor to Robert Frost, a poet who heightened the common language of ordinary people, who drew on the resources of pastoral verse going back to the Greeks and Romans. He quickened our sense of daily life, putting the work of digging peat or making horseshoes or plowing fields at the center of his poetry. His linguistic skills were both unique and, like that of any major poet, beyond comprehension, as he had access to the original springs of the language, watered by its deepest roots.

I first read him as a student at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, and I wrote to him at once. (We had a mutual friend in Glasgow, and that made the connection easy.) Not long after, Seamus visited me in Scotland, reading to a group of students I’d drawn together. I visited him, soon after this, in Dublin, getting to know his wife, Marie, and meeting his young children. Our visits, though never frequent, continued over the next four decades. Only recently, he came to stay with me at my Vermont farmhouse, and we had long talks about poetry.

What struck me during our last visit was his incredible focus on poetry. He was thinking about George Herbert at the time, and he quoted whole poems verbatim. His interest in the details of versification startled me, though it should not have. I’d somehow forgotten how thoroughly obsessed he was, and how poetry was life for him. He lived in its swelling cadences, in the specific diction of poets he admired. Their ways and means with language fueled and propelled him into his own poetry, which involved a rich conversation with his favorite poets: Wordsworth, Frost and Hopkins, Donne and Herbert. Of course he knew Yeats backwards and forward. He also loved Dante and the Beowulf poet (his translations of their poetry remains peerless—though I wish he’d done a whole Inferno.) The range of his poetic affections is evident in all his writing.

But what matters, really, was the freshness of his entrance into poetry in the late sixties and seventies. Those first five or six books of his, with their palpable images and idiosyncratic rhythms, their diamond-bright diction, the sweetness and sadness of his subjects, all of this struck countless serious readers of poetry at the time with the force of revelation.

Seamus had mastered and made his own the traditional cadences and forms: blank verse, the sonnet, the rhyming quatrain. I don’t think any poet since Wordsworth and Frost had so freshened traditional forms, bringing a quality of attention to the work at hand that took away the reader’s breath. In “Personal Helicon,” from his first volume, Death of a Naturalist, he wrote about staring into wells as a child, fascinated by the “dark drop, the trapped sky, the smells / Of waterweed, fungus and dank moss.” The poem ends:

Now, to pry into roots, to finger slime,

To stare, big-eyed Narcissus, into some spring

Is beneath all adult dignity. I rhyme

To see myself, to set the darkness echoing.

This was his ars poetica, a poem that locates the origins of a poet’s art. His poetry was a divine echo-chamber, a place where he listened and watched, gathering what Frost called the “sound of sense” in a discrete and physical manner, amplifying his own voice by rhymes, working on countless linguistic and symbolic levels. His poems invited, and still demand, rereading. In fact, his best poems live in their rereading, as meanings accrue, year after year.

I watched with fascination as Seamus dug into the Irish soil, as a poet, finding in the bog a perfect simulacrum of his own art. “Bogland” is one of the finest of these, a poem about the endless layers of Irish history gathered in a bog, in a poem, in the word itself—almost any word, which is a palimpsest, a story of erasures that underlie the current writing. “Our unfenced country / Is bog that keeps crusting / Between the sights of the sun,” he wrote in that poem, which is both a meditation on the complications of Irish history, where every layer “seems camped on before,” and a visualization of his own art, which involved delving, “striking inwards / And downwards.”

He described his own poetic evolution in “Singing School” from North, a sequence of eloquent meditations on Irish history and its wrenching politics in terms of personal and artistic freedom. It’s not for nothing that the title of the sequence comes from Wordsworth’s Prelude, a poem about “the growth of a poet’s mind.” Two of the poems in that sequence seem, to me, peerless examples of Heaney: “A Constable Calls” and “Exposure,” the latter a poignant self-portrait of the poet in his room of thoughts, where he sits “weighing and weighing” what he calls his “responsible tristia.” He confesses to being “neither internee nor informer.” Rather, he was “an inner émigré.”

His long and productive journey continued through half a century, with countless triumphs of language and sensibility, always compressed and brilliant, like a horseshoe hammered out on the anvil of his writing desk and dipped in water: an image given luminous shape in “The Forge,” his fond recollection of an old blacksmith. One can hardly begin to think where to reread—the collected poems of Heaney constitutes a diverse and limitless body of work that calls to the ear and lightens the spirit, asking one to take seriously the work of poetry, which is to listen to “the music of what happens.” His poetry became, for him, what he called “a search for images and symbols adequate to our predicament.”

That last quotation comes from “Feeling into Words,” a lively essay in Preoccupations, his first of several vivid collections of essays on poetry. That Seamus should also be a great critic should surprise no one. He thought deeply about poetry, putting incredible pressure as a reader on the language before him—a pressure not unlike what he lavished on his own poems as writer.

He also became, over the decades, a public symbol of the poet. I remember a visit from him in 1980, when he had just burst onto the American scene as a kind of representative poet, taking a chair at Harvard. We had a long walk around a lake in New Hampshire one afternoon, and he worried aloud about being on what he called “the conveyor belt” of readings and appearances. He wondered if this activity would detract from his writing. It didn’t seem to have damaged the work, in fact, as he continually added to the storehouse, writing incisive, memorable poems in his later years, including the astringent poems of his final volume, Human Chain, which contains poems equal to anything he’d written before, such as “A Kite for Aibhín,” where he celebrates the kite of self, “Climbing and carrying, carrying farther, higher.”

As testimonies pour in, and they will, it will become evident that Seamus Heaney was, among other things, a humble and kind man who never lost sight of a friend, even a casual acquaintance. He modeled virtue in his bearing, always keeping in mind his dear wife, Marie, and his three children, each of whom he loved dearly. (I have a bright image in my head of Seamus giving a reading in his mid-thirties, with young children pushing between his knees at the podium. Indeed, he broke off one poem in the middle, saying: “Michael, do not bite!”)

In my early thirties, in the midst of what seemed at the time like a major life-crisis, I wrote to him about my problems. He wrote back immediately a long and consoling and deeply wise letter, and I often think of this as a turning point in my life. He was a life-affirming man who could listen, and who took seriously his role as friend and mentor—not just to me but, in my experience of him, countless people who came into his radiant sphere of being.

Seamus Heaney was a rare and beautiful man, a poet of astonishing and incalculable gifts, a friend to so many, including myself. May he rest in peace.

*A version of Jay Parini’s tribute previously appeared in The Telegraph.

Seamus Heaney. I was slow in discovering the beauty of his poetry. Not enough ecstatic power, I thought in my earlier years. So sober, so poised, so realistic. So down to earth. This was when I tried to liberate my own writing from similar adjectives (plus “angry”, “critical”, “political”).

Another Irish poet was then one of my main gods: W.B.Yeats. Certainly not very sober though not lacking in political references. But how high they flew—like the Irish airman in the instant of his death. I traveled with Yeats to Byzantium and read several historical books trying to understand what kind of spiritual riches there were making this imaginary trip worthwhile. Opinions were divided and still are. The enigmatic, immobile Byzantium thrived in Yeats’ poem; when you’re in Istanbul or in a good library you can have your doubts (Joseph Brodsky certainly did not hide his).

But I kept returning to Seamus Haney’s poems. At some point we met and he became Seamus since. A warm, witty, friendly man, his comportment a perfect match to his fame—by which I mean that he was modest. Thus Seamus invalidated Goethe’s well known saying “Only knaves are modest.”

We met at Harvard at a reading arranged for me by Stanisław Barańczak in the late eighties. Then I saw him—twice, I think—in Houston where he had been invited by the University of Houston writing program and by Inprint, a group of Houstonians supporting literature. I liked this, being one of his hosts, driving him through the labyrinth of Houston—in Texas, not far from Galveston about which Apollinaire, who never came to America, wrote a lovely poem.

In 2005 he received an honorary degree from my alma mater, the Jagiellonian University in Krakow; by then he must have been used to honors but was not jaded at all. He prepared a beautiful essay which he read as his acceptance speech. The other person who on this very day was given the honorary title was Bronisław Geremek, one of Poland’s brightest Solidarity activists and an eminent medieval historian whose double vocation spanning civil society and marginal people in medieval Paris must have intrigued Seamus and reminded him of some of his own predicaments and dilemmas.

It was moving to see these two men together: both emerged as intellects and souls in times of trouble for their nations and both stood for moderation, for civilization, for a quiet courage.

And I did continue to read Seamus’ poetry, for myself and with my American students. Slowly it opened up for me, slowly I understood its multi-layered structure, its hushed visionary dimension. Along with the wonderfully intelligent essays Seamus had written, his poetic work has become a part of my indispensable library. Now I know: there’s no deficit of ecstatic power in his poems but this ingredient is compressed and controlled by other forces. The scale of this poetry is immense: from the quasi-demonic element present in the bog poems to a calm contemplation of the Irish seaside. There’s sense in humor in his poems and a tragic awareness of the “crooked timber of humanity.” There’s strong consciousness of the importance of form, of poetic forms—but never sheer aestheticism.

His is a poetry of a full human being. It’s easier to say farewell to artists who were obnoxious people; then it’s possible to accept that from now on only their work will stay with us. Seamus Heaney was a model of decency, an honest and charming man. We’ll have his poems but we’ll miss him, his smile, his wit, his goodness.

In July of 1995, a couple of months before Seamus got the Nobel Prize, my wife and I had flown from London to Dublin for a few days. A reading had been arranged by Peter Sirr and Chris Agee for me. Seamus came, as did John Montague, the Guelph and the Ghibelline, and then we all went to a lawn party. Seamus said he wanted to take me to see the grave of Gerard Manley Hopkins the next day. I was very excited as it was, strangely enough, the one place I wanted to see in Dublin.

The next day he came by our hotel and drove us to Glasnevin Cemetery, saying he couldn’t stay as he had to go prepare the introductions (all of them) for a benefit reading for Gallery Press, a Dublin Institution, but we could get a taxi back and we would meet that evening at his house to go out to supper. I was entranced by the communal Jesuit gravesite and looked at it long and hard, much moved. When we got to the Heaney house, Marie answered the door, saying Seamus would be right down. I couldn’t contain myself so immediately I launched into my story about Seamus taking the time to take me out to the cemetery. Marie said, “Ah, sure, he takes everybody out there.” Deflation City, but I was still glad to be in such a long and distinguished line of visitors. After supper, Seamus drove us around “Literary Dublin,” pointing out this and that, something he had obviously done countless times before. Such a magical day, such a magical man, always going out of his way for someone else. I hope someone will get the thrill of being taken to his grave some time in the years to come. Rest easy, sweet Derry Lad, rest easy.

Seamus Heaney pointing out Gerard Manley Hopkins’ name on the communal Jesuit grave at Glasnevin Cemetery, 2009, photo taken by Henri Cole

When I was in my twenties I studied theology at Harvard. I had the creeping sensation I was not going into ministry after I was finished. So what was I doing? I was unsure. I did love listening to and reading poetry. But that wasn’t a career, was it? My choices were starting to feel like mistakes. When I couldn’t stand reading theological treatises, which happened often, I would go over to the Poetry Room at Lamont Library and listen to poetry recordings on turntables. That should have indicated something. I’d often linger in the Grolier, as if the smell of poetry books would lead me in the right direction.

At the Divinity School, we had the option of taking one course outside the Yard in our curriculum. I remember opening the catalogue and seeing Seamus Heaney’s course: “British and Irish Poets: 1930-The Present.” I went immediately. I was searching for some kind of sign, like all those villagers in the Bible that start moving towards Christ, the one-man, miracle-healing celebrity. Curiously, poetry felt like a safer location for signs than theology. I think Heaney’s class was in Boylston Hall. It was an old lecture hall with high ceilings; it looked like a church sanctuary. There were windows on the right-hand side. Cambridge went by, animated with green trees and high-powered chatter. Everyone seemed confident. I’d studied literature in college, at Wesleyan, and now I’d come to this decision to study theology. Had I made the right decision? Poetry was irresistible to read, theology was work. At fifty, I see it all made sense eventually. I was in the right place, it just didn’t look like it yet.

Maybe the class had a hundred students? I can’t remember. I felt intimidated by all the undergraduates who seemed certain of things. Heaney’s lectures were mesmerizing from the minute he stood before us. He had a gift for lecturing, his Irish accent and deep voice lulled me. His mind was on full display for us: a mind that matched the chattering labyrinth of Cambridge. He wore tweed sport coats and Liberty print ties. His briefcase’s worn leather shone in the sunlight. His crop of snowy hair moved about the stage like an Irish cloud that rained insights every lecture. We studied Auden, Dylan Thomas, Louis MacNeice, Patrick Kavanagh, Medbh McGuckian, Michael Longley, Stevie Smith and many more. I had a thick light green Faber & Faber anthology for the class that I carried everywhere the way one holds onto their documents in foreign countries. His lectures were theater: he’d open his mouth and out came the lecture fully-formed without an “um” or a scatter-brained pause to be found. I took notes like a court reporter.

He was the best lecturer I had. I wanted to speak to Heaney but I never did. I was shy. I saw him at the movies when Joyce’s The Dead was put to film. I saw him through the crack of his office door. But I never said a word to him. Given how many modern Irish people feel distrustful of church, I assumed it best left unsaid that I was a Divinity School student studying poems.

In Luke, ten lepers get healed by Christ but only one turns around to say thank you. Thirty years ago, I was in the horde of nine healed mute lepers. Now that I am older, I take this chance to turn around and say to Heaney: “Thank you.”

Heaney recited the poems as I recall—a preacher without notes. The poetry was in him like religion was in my seminary friends. I remember him reciting “The Linen Workers” by Longley: Christ’s resurrection is compared with Protestant linen workers who were gunned down during the Troubles. With his wit and wisdom, the vexing history of Ireland in him, his love of words, he was pointing the way for my life—where Christ and poetry would meet.

I can’t claim to have been a friend; acolyte probably says it best, though I did occasionally meet him, and always felt the willingness to connect that he seemed to have in limitless supply. The last time I saw him and Marie, at an Ovid event in Rome this past May, Marie told me a poignant story. They had been traveling—making the usual rounds of readings and lectures and receptions crowded with well-wishers. One night as she was lying awake she heard Seamus say in his sleep, “now where did I meet you before?” The strain of the laureate’s social obligations had obviously gone deep, but what I find touching and revealing is how equally deep the grain of answering warmth also went. Even in sleep he met the pressures of the world with grace. I think there’s a clue there as to why, above and beyond the admiration compelled by its moral intelligence and verbal beauty, his poetry has the rare capacity for inspiring love. Speaking for myself, there’s no poet, living or dead, I’ve felt drawn to more constantly or devotedly, or with greater affection. I suspect I am not alone.

Dear Seamus. He took the English language, and returned it to us with startling new (and ancient) savors and textures. He made poetry into touching tongues. Here are some morsels from his prose, to give a taste of the feast: “exactions,” “resources,” “intellectual reconnaissance,” “keeps faith,” “covenant,” “pitch and scald,” “command,” “venturesome,” “spontaneous at-homeness in speech itself,” “skim factor” . . . There’s a whole world in these words.

“Is there distance in his head?” The line is from “St Kevin and the Blackbird,” Seamus’s sketch of the Irish monk who sticks a hand out the window of his cell and winds up cradling a blackbird and its quickening eggs, either “self-forgetful or in agony all the time” but made whole, and holy, by the effort. Like so many Heaney poems, it is a compact ars poetica, and that rabbinically strange question—“Is there distance in his head?”—points to a quality that made Seamus’s poetry so vital for so many of us who were simply his readers, not his fellow poets or his friends. To spot him in the hallway at the FSG offices was to see an eminence in the topographic sense of the word, a natural wonder just come from breakfast with Roger and Jonathan. To hear him tell St. Kevin’s story in his Nobel lecture, where he connected the story to Co. Wicklow, to the fraudulent Norman historian Giraldus Cambrensis, to Orpheus, and to the laureate sitting at his desk—“at the intersection of the natural process and the glimpsed ideal”— was to glimpse the distances he covered in his work, which joined his Irish ancestors to his readers around the world. “The prophet” (Flannery O’Connor declared) “is a realist of distances.” Heaney’s long prominence means that other writers have ventured already into the clearings he made. Now he is gone, survived by his poetry, and we will begin to see and feel the distances he saw and felt as if from the beginning.

In closing, we’d like to share Seamus Heaney reading his poem “St Kevin and the Blackbird” from The Spirit Level on Ireland’s “The Late Late Show.”