William came up out of the mortuary feeling blown out, depressed. He could not say if Charlotte Reckitt had deserved her end and he told himself he did not care but it was not true. He thought of her ravaged scalp and the tufts of hair and blood on it and how her body had been cut up and the legs still, for god’s sake, missing. Then he could not stop himself and thought of his daughters in Chicago, thought of Margaret. Swore under his breath and clapped his hands on his sleeves as if to dislodge the reek of the dead and stepped out into the fog.

opens in a new window |

Frith Street felt desolate in its brightness, the pale shapes swirling past, the cold mournful cries of costermongers in the mists. He could hear the lurch and creak of an omnibus over the cobblestones, the shout of a patterer trotting along behind it with his broadsides clutched in both arms, the soft tack-tack-tack of an undertaker’s hammer several shops down. He pinched his eyes shut, lifted the brim of his silk hat, ran two fingers along his hot scalp. He could see the vague grey trees in Soho Square to the north. His shadowy self moving like water in the shop windows as he passed. At the entrance to an arcade he slipped among a crowd and made his way between the wooden pillars and mud-stained carts, past rickety tables with

bolts of fabric laid out, past rows of folded spectacles, steaming pies, ball-peen hammers, inks, sheaves of paper, gloves and bonnets and stoles. He felt incandescent, and thin, as if not quite there. Men in stained cravats were calling out to him in the crush. Liverspotted hands in fingerless catch-alls clawed at his sleeves, grasped his wrists. He shook them off.

And then all at once he spun and jerked his right hand swiftly to his watch pocket and seized the small grubby wrist descending there.

She was a young pickpocket in a green bustle and a green bonnet and a strand of long brown hair had come unpinned at her throat. She looked tired and malnourished to his eye, her skin glassy, the blue veins visible in her forehead. He glanced out over the crowds but if any accomplice lurked there he did not see one. She clutched in her free hand a tiny kid glove of fine grey leather and her sunken eyes were frightened. He watched her writhe at the end of his grip like the eels he had seen hooked from buckets in the fish markets of New Orleans during the war and he glowered but did not have the heart to do more.

He let her go.

She stepped back without a word and rubbed her reddening wrist where his strong fingers had marked her and then she tugged back on the tight kidskin glove in a fury. When she looked at him her mouth was twisted to an ugly shape. Then she was gone in the crowd.

He stared at the space where she had stood and he thought of Charlotte Reckitt, startled by the sadness blooming inside him.

It was time he got out of London. He had come to this city trusting the Agency could run itself for two weeks but those two weeks had stretched to six and still he had come no closer to finding Shade. Sally Porter was right. Whatever Edward Shade had been to his father, he did not have to become that again.

But he made his way to the curb despite all of this and hailed a passing brougham through the fog and called ahead to the

driver: Hampstead, man.

Knowing if Charlotte Reckitt had left any clue to the ghost of Edward Shade it would be there, in that tall gloomy terraced house where she had lived.

• • •

It was an ancient brougham with the box and bench uncovered and its strange outsized wheels hulking up on each corner. William huddled on the damp seat, staring at the driver’s broad back, cursing his luck. The springs on the back wheels had known better days and on the uneven streets he ground his teeth and gripped the rail and felt his bones jar with the violence of it. The driver’s hair was long and lay plastered in greasy strands over his collar. William looked away.

He changed his mind at New Oxford Street and had the brougham turn down past the Strand. At the Union Telegram Office near the Embankment he climbed out and paid the driver and went in rubbing the back of his neck stiffly. A warm dank fug of cigar smoke came over him. The Office resembled a small bank with its pillared entrance and its tall carved doors and the long counter along one wall just under the windows. William went to the standing desk and withdrew a slip of paper and a pencil from the mesh cubby and wrote out a message to his wife in Chicago. It said, simply: PUNCHED OUT. OFF THE CLOCK. HOME SOON.

He licked the tip of the pencil and counted off the letters in their small boxes and then set the pencil down and stood in line at the counter. There were silk ropes marking out the waiting area and the marble floor gleamed underfoot and the counter and railings and window trims were a deep polished oak as if reclaimed from a wrecked schooner. The telegraph clerk was a young man with a green eyeshade set high on his forehead and he reminded William of the dealers in the card dens he had haunted in the Panhandle some years ago though the

man’s fingernails were too clean and his skin too soft.

He wrote out his home address in Chicago and the clerk glanced at him and back at the name Pinkerton printed there and then back at him but said nothing. His business was his alone. He opened his billfold and withdrew a five-pound note. When he came out the brougham stood at the curb yet and he paused and looked up the street in either direction but could see neither hansom nor carriage for the fog and he sighed and rubbed his neck and climbed creaking back onto the footboard.

Once again, guv? the driver grinned back at him. We was waitin for you. Just in case, like.

Wonderful, William muttered.

Hampstead?

William nodded and looked down at the cobblestones, at the brougham’s big old iron-shod wheels standing at the ready. Driver, he called up.

The man half turned on his bench, blinking.

I’m in no rush, he said.

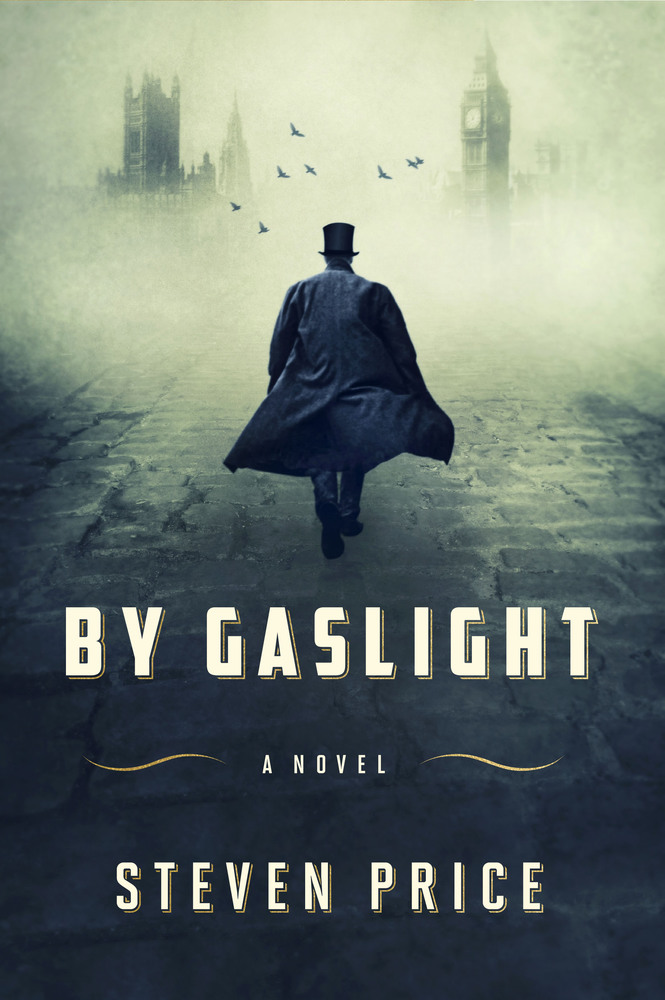

Steven Price‘s first collection of poems, Anatomy of Keys (2006), won Canada’s 2007 Gerald Lampert Award for Best First Collection, was short-listed for the BC Poetry Prize, and was named a Globe and Mail Book of the Year. His first novel, Into That Darkness (2011), was short-listed for the 2012 BC Fiction Prize. His second collection of poems, Omens in the Year of the Ox (2012), won the 2013 ReLit Award. He lives in Victoria, British Columbia, with his family.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE:

Jamie James on The Many Faces of Isabelle Eberhardt

The Mystery Behind the Woman who was Given Van Gogh’s Ear

Unforbidden Pleasures: Adam Phillips & Ilene Smith Discuss Agency and Desire

C.E. Morgan & Lisa Lucas Discuss the Politics of Storytelling