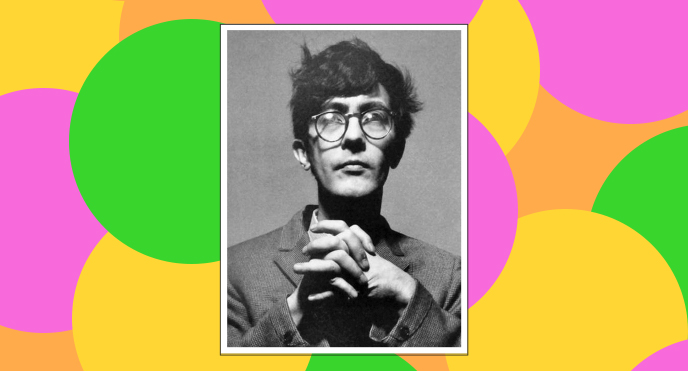

I’d been researching a biography of the late art dealer Richard Bellamy (1927–1998) for several years when he popped up in a dream. In waking hours, I tracked the man whom everybody called Dick through the postwar art world, perplexed by his absence from the grand narrative of late modernism. He survived in people’s memories, not in history books. Yet it was impossible to imagine the emergence of pop art, minimalism, conceptual art, and earthworks without this elusive, posterity-adverse impresario, who’d rather quote poetry than prices to collectors.

opens in a new window |

Dick grinned at me from a distance in my dream, waving what looked like a floppy footprint above his head. He was gone by the time I reached where he’d been standing. Half-buried at my feet lay not an inner sole, but a mask. Ha! Dick was an enigmatic, near-fictional character who lived his life as an ongoing performance, styling himself on Sir Gawain, Huckleberry Finn, and Miniver Cheevy.

In the early sixties, Dick directed the legendary Green Gallery on Fifty-Seventh Street, presenting artists with fresh answers to the question, “What is art?” “Don’t look at things that you immediately like,” he’d advised a young client. “Look at things that bother and agitate you. The things you don’t like challenge your brain.” He was the first to show Warhol’s pop paintings and Kusama’s phallus-studded sculpture. At the Green he launched the careers of pop artists Oldenburg, Rosenquist and Wesselmann; minimalists Judd, Flavin and Morris; as well as di Suvero, Segal, Samaras and Poons, mavericks all.

But it wasn’t Dick’s unsurpassed record as a scout that sustained my interest for the two decades I worked on his biography. It was his singular disdain for commerce. Money muddled the picture when looking at art, he felt. A latter-day Bartleby, Dick preferred not to profit from the mushrooming art market he helped to create. He’d grown up in comfort during the Depression in suburban Cincinnati, an outlier, the only child of a Chinese mother and an American father. Dick was already a heavy drinker when, by 1950, he’d settled in New York and embraced the Beat counterculture, befriended by Kerouac and Ginsberg. On his own, Dick never could have opened a gallery. The taxi magnate Robert Scull and his wife, Ethel, secretly backed the Green, a fact that contributed to their status as the nation’s first celebrity collectors.

Mention of Dick’s name granted me near-universal entrée to people whose lives he’d touched. I was particularly interested in talking to Yoko Ono—it was Dick who’d brokered her first art sale, to Scull. I was then living in London, where she agreed to see me. As an art history grad student in London thirty-three years earlier, I had seen Yoko’s eighty-minute film Bottoms, an audacious, mesmerizing sequence of 365 bare behinds in motion. I’d made it through ninety bums before slipping away.

I was disappointed when Yoko cancelled our meeting. Months later, she faxed me her recollections of Dick. She described seeing him at the Green, “standing straight with a casual authority of the ‘High Priest’ of the then New York art world, as he was hailed at the time in one of the big magazines.” He “understood and liked my work,” she said. When Dick called to say he’d sold her Sky Machine (a dispenser of cards reading “sky”), Yoko wrote that his “voice sounded peculiarly anti-climactic and distant, as if he had dreaded the thought of my expressing the joy with predictable female hysteria of shrieking into the phone, so to speak. He had no worry there. If anything, I was almost as Asiatic as he was. I just said, ‘Oh.’ That was how I was.”

My picture of their connection sharpened when Miles Bellamy shared a tantalizing letter Yoko wrote to his dad from London in December 1966. (Today it’s part of the Richard Bellamy Papers at the Museum of Modern Art.) Her first show in Europe had just closed, but she said little about it, and nothing about the evening of its preview, when she first met the winsome Liverpudlian who would soon change her life, and she, his. Yoko’s enigmatic Yes Painting, an apparently blank portion of the ceiling framed by a plane of glass, captivated John Lennon when he climbed a ladder to inspect it through an attached magnifying glass. He was relieved to discover that “it doesn’t say ‘no’ or ‘fuck you,’ it says, ‘yes.’”

Interest in Yoko’s work quickened in Europe at the end of 1966, but she was too broke to take advantage of the opportunities, she wrote to Dick. John Cage was also trying to help her and had suggested she stay at Peggy Guggenheim’s place during the upcoming holidays, but, she confided, “I don’t even have the money to go to Venice.” Dick no longer had a gallery. Eighteen months earlier, he’d closed the Green and stepped away from the high-stakes art market. He preferred working out of the limelight, backstage.

People like Cage assumed that without the Green, Dick had stopped doing business, but he continued working on Yoko’s behalf. He himself could make do with next to nothing, but when artists were in need, Dick did everything he could to find the the funds they needed to sustain themselves. Dick “was arranging things for me in NY,” Yoko’d told Cage, who was surprised and “very happy to hear that [Dick was] still active.” He was her guru: “What step shall I take next?” she wrote at the end of her letter. “Please advise at your earliest convenience.” If Dick responded, no record survives. Dick treated Yoko as he did with many of the artists he handled—active at the onset, and loyal from a distance once they found their feet.

Dick remained in touch with Yoko and John into the early seventies, a bel ami who sold them two boxes by Joseph Cornell, and escorted John to Queens to visit the reclusive artist. Miles Bellamy inherited two delightful souvenirs of his dad’s friendship with the couple. One’s a playful note that may have accompanied flowers: “Yoko asked me to send you her love, John Lennon”; the other is a delightfully altered picture postcard of Arnold Böcklin’s Spring Evening (Two Nymphs Listen as Pan Plays on his Pipes), 1879. Lennon, who’d studied art before becoming a musician, switched out one nymph’s noggin for a tiny headshot of Yoko. He transformed Böcklin’s goat god into a self-portrait, with penned-in eyeglasses and musical notes floating off on the breeze. Like Dick, Lennon was an inveterate punster, and on the card’s reverse he drew a tiny bell and clapper right above “Bellamy.”

Judith E. Stein is a Philadelphia-based writer and curator who specializes in postwar American art. A former arts reviewer for NPR’s Fresh Air and Morning Edition, her writing has appeared in Art in America, The New York Times Book Review, and numerous museum publications. She is the recipient of a Pew Fellowship in the Arts in literary nonfiction and a Creative Capital/Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant. A graduate of Barnard College, she holds a doctorate in art history from the University of Pennsylvania.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

Dominic Smith on Forgeries and Figments

A Conversation between Hans Ulrich Obrist and Marina Abramović

Sometimes You Sing an Aria: In Conversation wtih C. E. Morgan and Lisa Lucas

Yuko Shimizu and Alex Merto on the Design of Lian Hearn’s The Tale of Shikanoko