Joan Didion is one of the most distinctive and celebrated critical voices of our time. FSG published three of her most acclaimed books: the novel Play It As It Lays, and the searing essay collections Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album.

Tracy Daugherty’s expansive new biography, The Last Love Song, available on August 25 from St. Martin’s Press, takes an immersing look at the writer’s life, from her early adulthood struggling in New York to her loving, tumultuous marriage and her later critical success. The excerpt below provides a window into Didion’s world just after the publication of Play It As It Lays, as her reputation as one of the greatest living writers was beginning to take hold.

opens in a new window |

Didion was enamored not of the ocean but of the “look of the horizon . . . It is always there, flat.” If she was no longer physically comfortable in the Central Valley, she needed the solacing feel of her childhood geography. Each day ended fast, no muss—a snuffing of the sun in the sea, a healthy glass of bourbon. She felt Malibu was “a new kind of life. We were living on the frontier, as it were.” She had her husband and her sheepdog and her barefoot child getting splinters in her heels on the redwood deck. She had hurricane lamps, her family’s rosewood piano (it had sailed around the Cape in 1848), her grandmother’s hanging quilts sewn on a covered wagon, and a Federal table once owned by her husband’s great-great-grandmother. She had her mother’s Craftsman dinner knives. She had straight-backed wooden chairs hand-painted by her mother-in-law, shipped from Connecticut. She had, on her wall, a large black-and-white photo of a stark valley roadside with a sign pointing to Sacramento, and she had Eve Babitz’s Ginger Baker poster above the tub in the bathroom.

Tucked into the frame, behind another picture, she found a note to her in Noel’s handwriting—the one he’d left on his earlier visit: “You were wrong.” What about? Everything, no doubt. She burned the note and didn’t tell her husband about it.

Just outside the window of the room she used as her office, she hung the family’s clothes on a line to dry in the salt wind: her comfy old fisherman’s sweater, her husband’s blue extra- large bathrobe, her daughter’s black wool challis dress. She liked a small, enclosed space in which to write—surrounding herself with talismans of the latest project: postcards, maps, trinkets, and shells. (Her husband spread his books around a fourteen-foot table in a large library opening onto the ocean.) She liked the clothes outside, warm sleeves flapping—gentle puffs of breath—curtaining her view. She liked it that she could barely hear her own voice, sometimes, over the crashing of water on the boulders below.

Often at dinner she’d place a white orchid in her hair—her hair lightly reddened, lightly blonded by the sun.

She felt comforted by the crystalline stars appearing one by one over kelp-cluttered sea foam.

Her daughter went to sleep to the sound of the waves and awoke whenever the surf went silent at the tide’s lowest ebb.

The elements aligned for happiness.

Maybe the sixties really were over. The riots on Sunset Strip had petered out soon after Huey Newton went to prison: “Free the Strip! Free Huey!” Peace, then. It all seemed so distant. Miles down the road.

Cielo Drive. The Landmark Motel. Such an evil time. In the rearview mirror.

Now: the straight road ahead. Her husband had taken a full physical (for his insurance policy). Everything normal: prostate, EKG, EEG. The doctor had told him, in passing, he had “soft shoulders,” but that wasn’t a medical condition, and if this was the worst he could say, well then . . . bring on the breakers!

And she . . . “I was so unhappy” writing Play It As It Lays, she admitted now to friends. “I didn’t realize until I finished it how depressed it had made me to write it. Then I finished it and suddenly it was like having something lifted from the top of my head, you know? Suddenly I was a happy person.” People “were talking about this book. Not in a huge way, but in a way I hadn’t experienced before. It made me feel good. It made me feel closer to it. . . . [F]rom that time on I had more confidence.”

opens in a new window |

And why not?

James Dickey had called her, in print, “the finest woman prose stylist writing in English today.”

Her old teacher Mark Schorer had said, “One thinks of the great performers—in ballet, opera, circuses. Miss Didion, it seems to me, is blessed with everything.”

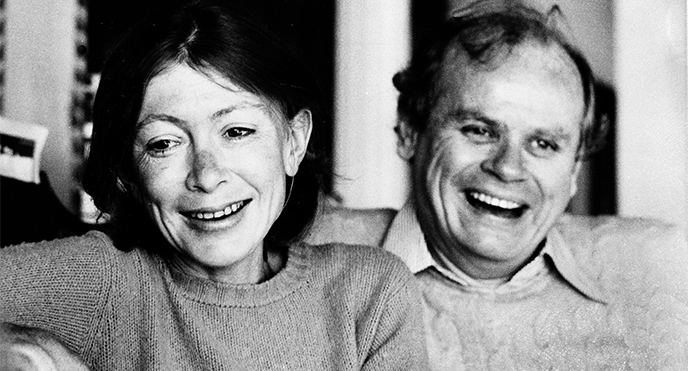

Alfred Kazin flew from New York to interview her for Harper’s magazine. The day he arrived, a small wildfire flared in the canyon hills, but this didn’t stop surfers from lugging their boards to the ocean and riding the swells under an angry canopy of red-black ash. Kazin invited Didion to lunch at Scandia on the Strip, annoyed when Dunne came along. The couple seemed inseparable—in his journal, Kazin noted an almost constant electric “ripple” between them.

Dunne dominated the conversation, telling Kazin that California was the best place a writer could be to chronicle the American scene. He said Nixon was the “most interesting personality in the White House since FDR,” and he told Kazin he thought “one of these days the President will crack in public.”

After eating, they all drove back to Malibu. “People who live in a beach house don’t know how wary it makes them,” Kazin wrote. Didion’s decision to move here, to keep an eye on the edge, told him she was a “very vulnerable, very defensive young woman whose style in all things is somehow to keep the world off, to keep it from eating her up, and so”—casting protective spells—“[she] describes Southern California in terms of fire, rattlesnakes, cave-ins, earthquakes, the indifference to other people’s disasters, and the terrible wind called the Santa Ana.”

In the magazine piece, he characterized Didion as “subtle,” as possessing an “alarmed fragility,” and falling into “many silences.” In his private journal, he said she was “full of body language. . . . Her face runs the gamut from poor old Sookie to the temptress with long blonde-red locks. She can look at you and past you without the slightest hint of a concession. The unspoken is a most important part of her presence in the world.”

She was trying to tell him, This is what a happy woman looks like.

Tracy Daugherty is the author of four novels, four short story collections, and a book of personal essays. His critically acclaimed biography of Donald Barthelme, Hiding Man, was published in 2009. He has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. Currently he is Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing at Oregon State University.