Living inside a book for many years it is perhaps inevitable that one loses sight of what the book is actually about. That is, if one ever really knew in the first place. Writers move stealthily, and almost always by instinct. However on completing a manuscript one is forced to describe to agents, editors, friends, and family the subject-matter of these months and years of furtiveness. So, what is your book about? It’s at this point that the full extent of the myopia is laid bare. “I’m afraid I’m not sure” will not suffice as an answer. Neither will, “Can you give me a little more time to disengage myself and make sense of things?” In the end I usually find myself talking about what led me to the book, for this is a subject I can tip-toe around with some degree of confidence.

opens in a new window |

My northern childhood was far from idyllic. I was the child of young parents who, full of cautious optimism, migrated from the Caribbean to Britain in the late fifties and subsequently encountered a grey, not always welcoming country which, a little over a decade after the end of the Second World War, still bore the scars of the German bombing campaign. It’s now axiomatic that Post-Suez Britain was becoming unsure of her role in the world, and perhaps as a result the country was deeply suspicious of the seemingly endless wave of black and brown colonial arrivants. My parents stepped off their particular ship at Newhaven on July 12, 1958, and only a few weeks later race riots erupted in London, Nottingham, and other parts of Britain. My mother had a sister who had made the passage a year earlier and settled in Leeds, and so my parents followed suit. They headed north and attempted to find shelter and employment and build a future in the heart of industrial Yorkshire.

Stories of idyllic English childhoods seldom offer up images of cobbled streets, bellowing chimney stacks, flat caps, rag and bone men, and murky, polluted canals. Such scenes, however, form the backdrop of the upsurge of postwar northern fiction by the likes of John Braine, Stan Barstow, David Storey, Shelagh Delaney, and others, whose gritty social realism was often quickly transferred to the screen in films which usually starred the angular, fag-puffing Albert Finney, Tom Courtenay, or Richard Harris. This created in the national consciousness a picture of northern hardscrabble, hand-to-mouth lives that were a long way away from Arcadian picnics on sun-kissed grassy river banks with cream cakes and lashings of ginger beer. I suspect that, like a good number of northern kids, I read far too many of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five books, and Anthony Buckeridge’s Jennings series searching for a more bucolic alternative to the childhood I was living. The truth is, I didn’t consider myself to be in any way deprived; I just suspected that somewhere—down south—there were others who had more than I did of pretty much everything—including fun.

In the sixties Britain began to emerge from behind a grey and somewhat miserable postwar cloud. Legislation effectively abolished censorship in the theatre, and abortion and homosexuality were no longer deemed criminal activities. Skirts got shorter, hair longer, a football World Cup was won, but I was a child and only later came to understand the significance of these sunny developments. Truthfully my own sixties childhood never really emerged from behind that grey cloud, and two disturbing events dominate my recollection of growing up in the north of England. I recall one event with worrying clarity; the other I have tried hard over the years to forget. I remember whispered adult conversations about Ian Brady and Myra Hindley—the Moors murderers. A decade or so later, when I was a brooding adolescent trying to hide from my parents and lose myself in literature, the forbidding moors came back into view courtesy of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. To my mind, both off the page and on it, the ethereal, shadowy, moors bespoke danger. I remember searches for bodies on the television news and disturbing photographs in newspapers, and although the evil culprits were apprehended I was acutely aware that all the bodies were never discovered and there was therefore no real closure to this unspeakably malevolent episode.

I have great difficulty recalling the other event that hovers uncomfortably over my childhood. For a person who has spent many years writing about the importance of understanding the past it is quite shocking the degree to which I have almost completely misplaced the two weeks I spent at Silverdale on the Lancashire coast, at a camp for underprivileged children. Five years ago I sat down to try and begin work on a novel that I knew would, in part, be set on the moors between Yorkshire and Lancashire and would have some echoes of sitting alone reading Emily Brontë and childhood fears of Brady and Hindley. However this lost fortnight kept trying to intrude into my narrative, but without any tangible facts to give it any shape or substance. At this juncture I temporarily became less of a writer and more of a researcher. A cursory perusal of the internet revealed that Leeds City Council still organized trips to Silverdale for underprivileged children. I soon discovered that I was actually able to look at pictures of the place, but only a few very vague memories came flickering back to me, and nothing that might bear the weight of narrative. It was then my good fortune to stumble upon the Leeds-born author Keith Waterhouse’s memoir, City Lights.

The first chapter of City Lights begins: “In the stifling August of 1936 the black American athlete Jesse Owens arrived in Berlin to claim four gold medals at Hitler’s Olympic Games . . . and I, aged seven and a half, set off on an expedition to a faraway country, clutching a borrowed cardboard suitcase.” Waterhouse’s journey began outside the offices of the “Leeds Poor Children’s Holiday Camp Association” and ended at the camp itself at Silverdale on “a grassy promontory inhabited only by gulls and temporary orphans, overlooking Morecambe Bay.” Some thirty years later, I too stood outside the same offices, although I’m fairly sure that by then the word “Poor” had been dropped by the city council. I have no idea whether it’s replacement was in fact “underprivileged,” but it must have been blatantly transparent to any onlooker that this assemblage of kids were the sort who received free school dinners and whose school blazers always looked either a little too small or a bit too big. Unlike me, Keith Waterhouse displays an almost perfect recollection of his two weeks in his opening chapter. He remembers standing outside of the offices and feeling “terrified;” he remembers the journey across the moors singing the unofficial camp song.

There is a happy land, far, far away,

Where they have jam and bread three times a day,

Eggs and bacon they don’t see,

They get no sugar in their tea,

Miles from the familee, far, far, away.

He remembers arriving at a place that looked like a prisoner-of-war camp, and “had the air of being surrounded by barbed wire.” Reading this opening chapter my own painful memories began to surface, and it was apparent to me why, over the years, I had vigorously repressed them. As Waterhouse makes clear, “Silverdale was no place for misfits, loners or urban agoraphobics,” and while the camp in fact may evoke happy memories for some children, reading City Lights simply confirmed that I was not alone in imagining that particular fortnight of abandonment to be an undeniably miserable part of my childhood.

City Lights, with its opening chapter of loneliness and the wretchedness of incarceration, led me back to Wuthering Heights, which in turn led me back to the moors, which inevitably evoked uncomfortable memories of Brady and Hindley, and a pattern began to emerge of landscape and lost children, and broken parental ties, and familial pain and discomfort. Suddenly life was feeding literature, and literature feeding life, and once I put aside researching and returned to writing I found myself better able to focus on the characters, and the language and narrative texture of the book. Soon there were four Post-its on my desk, each containing a single word. Yorkshire. Moor. Lost. Child. And as I continued to write, another Post-it eventually fell gingerly into place with a fifth word upon it, Literature, a word which spoke to the presence of Emily Brontë as one entryway into my book, and surprisingly enough Keith Waterhouse as another gateway. Both his memoir and her novel, in their different ways, seemed to be calling to the small boy who had arrived in his parents’ arms in the Britain of the late fifties and travelled north to a city that is situated in the long shadowy penumbra of the moors. All that was left was for me to write my own book and tell an altogether different story.

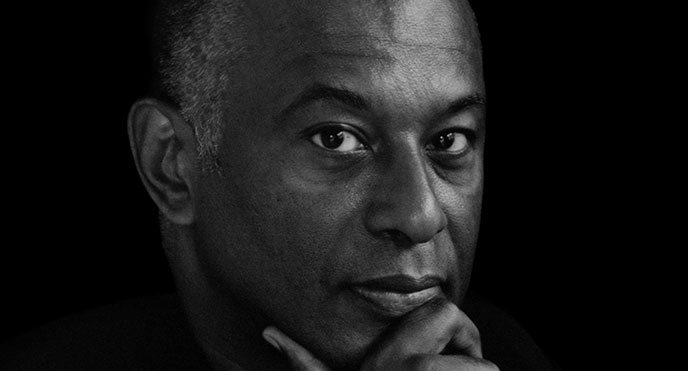

Caryl Phillips is the author of numerous works of fiction and nonfiction including Dancing in the Dark, Crossing the River, and Color Me English. His novel A Distant Shore won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, and his other awards include a Lannan Foundation Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and Britain’s oldest literary award the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. He is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and lives in New York.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

An excerpt from The Lost Child by Caryl Phillips

In Lieu of Winning the Lottery: Paul Beatty & Colin Dickerman in Conversation

What, Exactly, Have You Been Doing for the Past 14 Years? by Arthur Bradford