Even now, the voice that announces itself in the opening line of “Herbert White,” the first poem in Frank Bidart’s first collection, Golden State—“When I hit her on the head, it was good”—shocks and unnerves me, its force undulled by fifteen years of rereading. And the poem still ranks as the bravest debut I know, presenting the first-person confession of a child-murdering necrophiliac without any introduction or narrative frame, with only quotation marks to distance the writer from the story that follows.

But if “Herbert White” merely shocked and unnerved, I wouldn’t return to it so often. What astonishes me about the poem is the moral high-wire act Bidart performs. On the one hand, even as we inhabit Herbert White’s unhinged consciousness, the poem never occludes the horror of his crimes; it never lets us forget his victims (“and I saw, / under me, a little girl was just lying there in the mud”); it never allows him any of the glamour that so often accompanies representations of violence.

And yet it also never allows us to deny White his human personhood, or to fully exclude him from the circle of our sympathy. “You see, ever since I was a kid I wanted / to feel things make sense,” he says; he feels “suffocated by the asphalt; / and grass; and trees; and glass; / just there, just there, doing nothing! / not saying anything!” His actions follow from his need “to see beneath it, cut // beneath it, and make it / somehow, come alive…”

I’m still terrified by the shock of recognition I feel reading those lines, which deny voyeurism and force the acknowledgment of something like kinship. “Herbert White” is finally a portrait of the artist, or a portrait of the artist’s shadow. He is the nightmare double that—given who knows what frustrations or deprivations, or who knows what poisoned ground—the impulse toward art, the desire “to feel things make sense,” can lead to.

And so “Herbert White” announces the stakes of art as Bidart conceives them. What do we do with our need for meaning, with our forever denied demand for the world to crack open and reveal to us some hidden significance? “Man needs a metaphysics,” Bidart writes in “Confessional,” a poem from his third collection; “he cannot have one.”

Bidart has worried this knot for over four decades, in poems that have ranged from his family history (“Golden State”) to psychoanalytic case studies (“Ellen West”), from Greek myth (“The Second Hour of the Night”) to—in a thrilling new long poem he read several months ago at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop—the story of Genghis Khan. His career has been at once restless, experimental, and remarkably consistent, with each book adding new resources to a voice whose essence has remained clear since the chilling opening line of “Herbert White.”

When I first encountered Bidart’s poems, they changed my sense of what literature can do, and of what I want to do in my own work. Each of his collections is a challenge, a reminder of the proper scale of artistic ambition. It isn’t enough to call him one of our finest poets; he is, for me, the most important living American writer.

—Garth Greenwell

Herbert White

“When I hit her on the head, it was good,

and then I did it to her a couple of times,—

but it was funny,—afterwards,

it was as if somebody else did it . . .

Everything flat, without sharpness, richness or line.

Still, I liked to drive past the woods where she lay,

tell the old lady and the kids I had to take a piss,

hop out and do it to her . . .

The whole buggy of them waiting for me

made me feel good;

but still, just like I knew all along,

she didn’t move.

When the body got too discomposed,

I’d just jack off, letting it fall on her . . .

—It sounds crazy, but I tell you

sometimes it was beautiful—; I don’t know how

to say it, but for a minute, everything was possible—;

and then,

then,—

well, like I said, she didn’t move: and I saw,

under me, a little girl was just lying there in the mud:

and I knew I couldn’t have done that,—

somebody else had to have done that,—

standing above her there,

in those ordinary, shitty leaves . . .

—One time, I went to see Dad in a motel where he was

staying with a woman; but she was gone;

you could smell the wine in the air; and he started,

real embarrassing, to cry . . .

He was still a little drunk,

and asked me to forgive him for

all he hadn’t done—; but, What the shit?

Who would have wanted to stay with Mom? with bastards

not even his own kids?

I got in the truck, and started to drive,

and saw a little girl—

who I picked up, hit on the head, and

screwed, and screwed, and screwed, and screwed, then

buried,

in the garden of the motel . . .

—You see, ever since I was a kid I wanted

to feel things make sense: I remember

looking out the window of my room back home,—

and being almost suffocated by the asphalt;

and grass; and trees; and glass;

just there, just there, doing nothing!

not saying anything! filling me up—

but also being a wall; dead, and stopping me;

—how I wanted to see beneath it, cut

beneath it, and make it

somehow, come alive . . .

The salt of the earth;

Mom once said, ‘Man’s spunk is the salt of the earth . . .’

—That night, at that Twenty-nine Palms Motel

I had passed a million times on the road, everything

fit together; was alright;

it seemed like

everything had to be there, like I had spent years

trying, and at last finally finished drawing this

huge circle . . .

—But then, suddenly I knew

somebody else did it, some bastard

had hurt a little girl—; the motel

I could see again, it had been

itself all the time, a lousy

pile of bricks, plaster, that didn’t seem to

have to be there,—but was, just by chance . . .

—Once, on the farm, when I was a kid,

I was screwing a goat; and the rope around his neck

when he tried to get away

pulled tight;—and just when I came,

he died . . .

I came back the next day; jacked off over his body;

but it didn’t do any good . . .

Mom once said:

‘Man’s spunk is the salt of the earth, and grows kids.’

I tried so hard to come; more pain than anything else;

but didn’t do any good . . .

—About six months ago, I heard Dad remarried,

so I drove over to Connecticut to see him and see

if he was happy.

She was twenty-five years younger than him:

she had lots of little kids, and I don’t know why,

I felt shaky . . .

I stopped in front of the address; and

snuck up to the window to look in . . .

—There he was, a kid

six months old on his lap, laughing

and bouncing the kid, happy in his old age

to play the papa after years of sleeping around,—

it twisted me up . . .

To think that what he wouldn’t give me,

he wanted to give them . . .

I could have killed the bastard . . .

—Naturally, I just got right back in the car,

and believe me, was determined, determined,

to head straight for home . . .

but the more I drove,

I kept thinking about getting a girl,

and the more I thought I shouldn’t do it,

the more I had to—

I saw her coming out of the movies,

saw she was alone, and

kept circling the blocks as she walked along them,

saying, ‘You’re going to leave her alone.’

‘You’re going to leave her alone.’

—The woods were scary!

As the seasons changed, and you saw more and more

of the skull show through, the nights became clearer,

and the buds,—erect, like nipples . . .

—But then, one night,

nothing worked . . .

Nothing in the sky

would blur like I wanted it to;

and I couldn’t, couldn’t,

get it to seem to me

that somebody else did it . . .

I tried, and tried, but there was just me there,

and her, and the sharp trees

saying, ‘That’s you standing there.

You’re . . .

just you.’

I hope I fry.

—Hell came when I saw

MYSELF . . .

and couldn’t stand

what I see . . .”

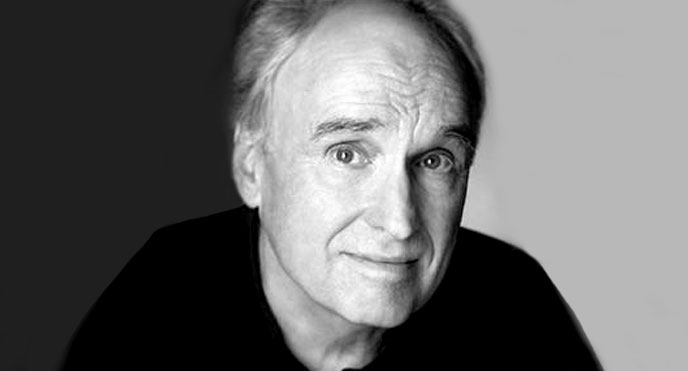

Frank Bidart’s recent full-length collections of poetry include Watching the Spring Festival (FSG, 2008), Star Dust (FSG, 2005), Desire (FSG, 1997), and In the Western Night: Collected Poems 1965–90 (FSG, 1990). He has won many prizes, including the Wallace Stevens Award, the 2007 Bollingen Prize for American Poetry and, most recently, the National Book Critics Circle Award for Metaphysical Dog. He teaches at Wellesley College and lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Garth Greenwell is an Arts Fellow at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His novella Mitko won the 2010 Miami University Press Novella Prize and was a finalist for the Edmund White Award for debut fiction and a Lambda Literary Award. His debut novel, What Belongs to You, will be published by FSG (January 2016).

Read all of our Poetry Month coverage here