When I read Derek Walcott it happens every third line or so. I wince with envy, pure and simple. Not the way Salieri was jealous of Mozart, more the way the bloke in the suit sits beside his date in the dark cinema, watching Fred Astaire dance a smooth dance. The galoot is itchy, knowing she’ll want some of that kind of grace later. All he will be able to muster will be nothing like that.

I grew up watching old movies and lots of TV shows. My mother took me to the movies and steered me away from the television. But I snuck home and watched, absorbing everything I could. I’m still amazed at how many scenes of the old Star Trek took place in the elevator, coming down off the bridge. They would get in there and Bones and Kirk would talk about Spock, or Nurse Chapel and Bones would talk about Kirk, or nobody would talk at all and they just look sneaky and askance at each other while a Klingon stared straight ahead, unaware that a big karate chop was coming. Probably more scenes happened in that elevator than in any other show ever. Instead of Star Trek it could have been called “the elevator show.”

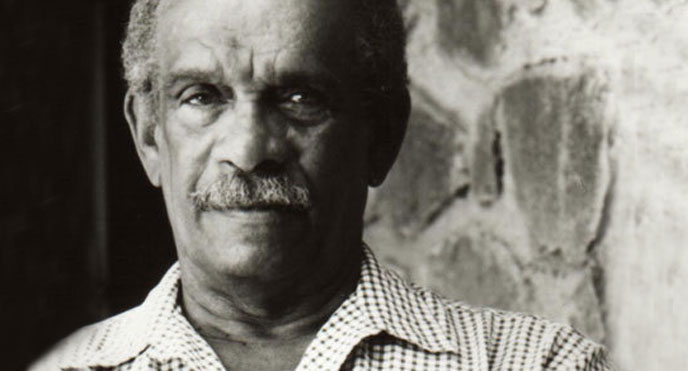

Derek Walcott is a Nobel Prize winner. That sort of thing always makes me nervous. But Walcott is so capable, you forget he’s a prize-winner, you forget everything about him; it’s just the two of you, and the island, and the sea, and New York on a summer day and a bird and a goddess and horseback riders in Africa and a painting on the wall. That’s it. A shared experience you never had before, a life you are leading as someone else.

If any other show had as many scenes in an elevator as Star Trek did, we would have talked about it, complained about it. “Why are those guys in Seinfeld always in the elevator?” or “Boy, Waterston sure gets a lot accomplished during those rides in the elevator.” But we don’t talk about it a lot when we talk about Star Trek.

Maybe it’s because he’s from an island and writes so well about the sea, but I like to believe that Derek Walcott knows how to tie more than a few kinds of knots. I think we all assume that if you know the right knots, you can make the world your own. Nothing is more simple than a piece of rope. Walcott takes the chunks of what surrounds you and sets them simply together, the sky looks like it looks and “the sea’s lace dries in the sun . . .”

There it is, just one example, the phrase deceptively simple, an act he does over and over again. It echoes far beyond whatever elevator you’re trapped in, through the elevator shaft, across that island where you’re currently residing, across the histories and far past the church, until you realize you are on a spaceship.

—Toby Barlow

The Sea Is History

Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs?

Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,

in that gray vault. The sea. The sea

has locked them up. The sea is History.

First, there was the heaving oil,

heavy as chaos;

then, like a light at the end of a tunnel,

the lantern of a caravel,

and that was Genesis.

Then there were the packed cries,

the shit, the moaning:

Exodus.

Bone soldered by coral to bone,

mosaics

mantled by the benediction of the shark’s shadow,

that was the Ark of the Covenant.

Then came from the plucked wires

of sunlight on the sea floor

the plangent harps of the Babylonian bondage,

as the white cowries clustered like manacles

on the drowned women,

and those were the ivory bracelets

of the Song of Solomon,

but the ocean kept turning blank pages

looking for History.

Then came the men with eyes heavy as anchors

who sank without tombs,

brigands who barbecued cattle,

leaving their charred ribs like palm leaves on the shore,

then the foaming, rabid maw

of the tidal wave swallowing Port Royal,

and that was Jonah,

but where is your Renaissance?

Sir, it is locked in them sea sands

out there past the reef’s moiling shelf,

where the men-o’-war floated down;

strop on these goggles, I’ll guide you there myself.

It’s all subtle and submarine,

through colonnades of coral,

past the gothic windows of sea fans

to where the crusty grouper, onyx-eyed,

blinks, weighted by its jewels, like a bald queen;

and these groined caves with barnacles

pitted like stone

are our cathedrals,

and the furnace before the hurricanes:

Gomorrah. Bones ground by windmills

into marl and cornmeal,

and that was Lamentations—

that was just Lamentations,

it was not History;

then came, like scum on the river’s drying lip,

the brown reeds of villages

mantling and congealing into towns,

and at evening, the midges’ choirs,

and above them, the spires

lancing the side of God

as His son set, and that was the New Testament.

Then came the white sisters clapping

to the waves’ progress,

and that was Emancipation—

jubilation, O jubilation—

vanishing swiftly

as the sea’s lace dries in the sun,

but that was not History,

that was only faith,

and then each rock broke into its own nation;

then came the synod of flies,

then came the secretarial heron,

then came the bullfrog bellowing for a vote,

fireflies with bright ideas

and bats like jetting ambassadors

and the mantis, like khaki police,

and the furred caterpillars of judges

examining each case closely,

and then in the dark ears of ferns

and in the salt chuckle of rocks

with their sea pools, there was the sound

like a rumor without any echo

of History, really beginning.

Derek Walcott was born in St. Lucia in 1930. He is the author of thirteen collections of poetry, seven collections of plays, and a book of essays. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1992.

Toby Barlow is the author of Babayaga and Sharp Teeth. He lives in Detroit.

Read all of our Poetry Month coverage here