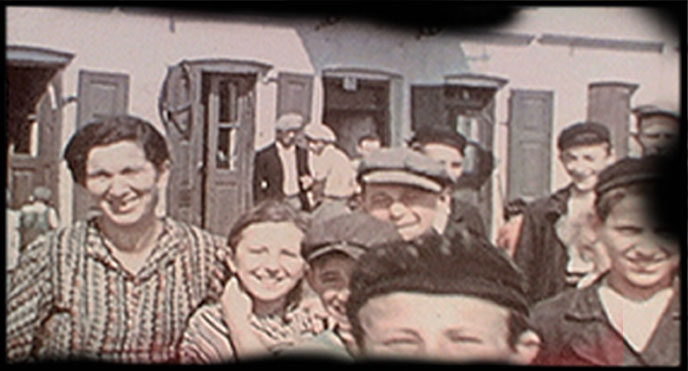

About four years ago, Glenn Kurtz discovered a film reel his grandfather shot in 1938 of the tiny, predominantly Jewish town of Nasielsk, Poland. Realizing that it was the only footage of this vibrant town before the Nazi occupation, Kurtz donated it to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum who made it available online. A few months later, he received a phone call from a young woman who explained that she recognized her grandfather in his film. Maurice Chandler now lives in Florida, but in 1938 he was a young, Jewish boy living in Poland, eager to be in the frame of David Kurtz’s film. Using Mr. Chandler’s story and those of other survivors, Kurtz breathes life back into this forgotten town with his new book Three Minutes in Poland. In the following excerpt, Mr. Chandler describes his escape from the Warsaw Ghetto in 1940 and the beginning of his remarkable journey of survival.

|

Morry, Avrum, Shiye Brzoza, Avruml Jedwab, and Shimon Kaminski escaped the Warsaw ghetto in the simplest, most dangerous way possible: they rode the streetcar. Because the Warsaw Ghetto occupied a central place in the city, tramlines available only to “Aryans” were introduced in November 1940, cutting across the ghetto territory. These “transit” lines had a police escort and did not stop in the ghetto. But sometime in the spring of 1941, Morry heard a rumor that the Polish policeman who rode on the steps of the streetcar would let Jews on for a bribe of five złotys. He and the other four boys decided to take a chance.

“My mother carried on,” Morry recalled in 1993, “‘No, no,’ she says. ‘We just got you back here. Mesiach wird kommen,’” the Messiah will come, “‘and the Germans can never win a war and it’s just a matter of time. Just stay with us and we’ll all together live to see Hitler go,’ and so on. It was terrible. But really, honestly, if you asked me when we left, did I ever expect never to see anybody again—I never thought that this was how it was going to work out.”

In his 1993 interview, Morry described the day of their escape. “I see that day like I’ll see it all my life,” he said. “I remember on that day a heavy snow fell on Warsaw—a blanket snow. The type of snow that falls in flakes this large, you know, and then eventually sloshes when it falls.”

• • •

Having escaped the ghetto, the next problem was to escape from the city of Warsaw. They had emerged onto the street above the Vistula River, which separates the city from the industrial suburb of Praga. The nearest crossing was the Poniatowski bridge. “So we went towards the bridge,” Morry continued in 2012. “And we had a quick meeting, Should we walk the bridge, or get in another streetcar? They had German guards at each side of the bridge, you know, it’s a strategic spot. But I said, ‘If we walk, it’ll look funny. Who walks a big bridge? So we might as well risk getting on the street car.’” In 1993, he had reported the conversation this way: “I said, ‘If we’re gonna play goyim, now we’re goyim. Let’s start realizing that we’re not on the inside and let’s start looking tough.’” They had been outside the ghetto walls for fifteen, perhaps thirty minutes.

“So we made it to the other end,” Morry told me. “And we got off, and we started walking away from Warsaw. That’s when we came to this farmhouse. And then we went further. And my brother and I got jobs as shepherds.”

In another conversation, Morry said the boys walked to the town of Kałuszyn, about forty miles due east of Warsaw. The boys may have walked this far that first day. Or they may have walked all night. Or stopped somewhere else, arriving in Kałuszyn the next day. It is impossible to reconstruct the experience in finer detail.

Months later, Morry recalled more about the farm where the boys stopped on the road out of Warsaw. “It was the same day. We ate, she gave us—the lady from the village, she had just baked hot loaves of bread, you know, a big loaf like this . . . And, we were all five of us—and you asked for some bread. And she cut off pieces. Hot! You know, it was—the aroma was killing us. And we gobbled it up with cold milk, and it took us like a hundred yards, our stomachs went crazy.” When Morry said, “We were all five of us—and you asked for some bread,” he left something out, which should also be part of the story. After a year and a half struggling to survive in the Warsaw Ghetto, what is missing from this sentence is very likely, And we were all five of us starving.

Within days of escaping, the five boys split up.

“When we first left the Ghetto, we wound up in that village, Wola,” Morry told me at the end of January 2013, a year after we had first met, “and we both got jobs.”

Wola Rafałowska is a village four and a half miles south of Kałuszyn. In May 1941, Jews were still permitted to live in the surrounding countryside. But the five boys could not find shelter together. Morry and Avrum found a place with the family of the village tailor. The other three boys set out on their own.

“Nobody made it,” Morry told me. He believes they soon returned to the Warsaw Ghetto.

Avruml Jedwab, Shimon Kaminski, and Shiye Brzoza are all listed in Yad Vashem’s Shoah victims’ database.

• • •

Morry continued working at Helena Jagodzińska’s farm until late summer 1942, when once more the order came for all Jews in the area to move into the local ghetto.

That May, Jews from Węgrów had formed part of the labor pool conscripted to build the Treblinka death camp. In the Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, the entry for Węgrów fills in the picture. “Suspicions about the camp heightened in July 1942 after forced laborers from Węgrów working there did not return home. In July, the wives of German military and police officials in Węgrów told Jews who worked for them to hide their valuables. Then, on August 24, 1942, posters were hung in Węgrów signed by [Ernst] Grams [Reich Economic Advisor and District Leader (Reichslandwirtschaftsrat and Kreishauptmann)] restricting access to Jewish neighborhoods only to registered residents and voiding all Jewish travel passes.”

In 1993, Morry described the scene this way: “Everybody was panic stricken, because there was no place to go and that’s it. This was the end. Everybody had to be in the ghetto and whoever by such and such date is not going to be in the ghetto, will be summarily shot.”

Morry, too, prepared to leave. But on the last day, Helena spoke to him, calling him by his Polish name. “She says, ‘Munya, what are you going to do? Where are you going to go?’ I said, ‘I think I’ve run out of places to go. I’ve been already all over. The roads are closed.’ I says, ‘I’ve got to go to the ghetto. I’m not going to go back to Warsaw, but I’ll go to the Węgrów ghetto.’ So, she says, ‘Well, we’re not going to go to a ghetto.’”

Around midnight, Helena’s nephew Stanisław Pachnik arrived. He worked at the county records office. He had stolen a narodziny, a birth certificate. Not fake papers, real papers, the original document from the files, the birth certificate of a Polish boy who had died. “Be it known that Zdzisław Pływacz was born on 21 January nineteen hundred twenty-three of father Bronisław and mother Janina of the house of Klaszka.” Certified authentic, signed, stamped. Perfect, except for the warning in large print in the upper right: “Original Document. Do Not Remove.” Morry and Pachnik tore off the corner. “We spent about an hour, folding it back and forth,” he said in October 2012, recalling that night. “They said, ‘you don’t have to go to the ghetto. You’ll have a new name. You don’t look Jewish. Your Polish is excellent. Try and be that person.’”

Glenn Kurtz is the author of Practicing: A Musician’s Return to Music and the host of Conversations on Practice, a series of public conversations about writing held at McNally Jackson Books in New York.