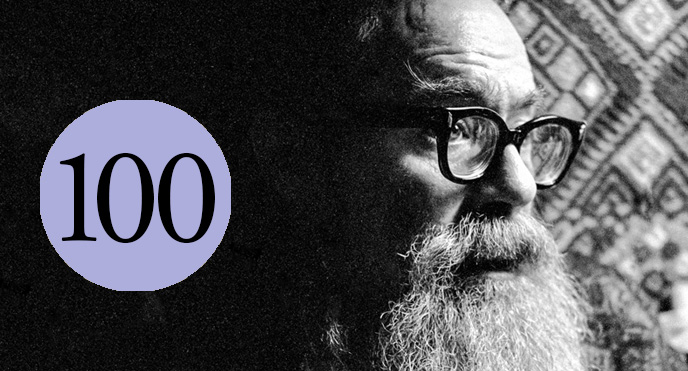

Rick Moody

In commemoration of the centenary of John Berryman’s birth (October 25, 1914), FSG’s Work in Progress is celebrating this icon of twentieth-century American literature by having authors write about what they admire about him and his work.

“A dream recounted is a reader lost” is how I have always recalled the Henry James quotation, though it seems each writer, afflicted with the hard truth of this line, remembers it in a different way. If the unconscious is structured like a language (to paraphrase Lacan), it is a very difficult tongue—like Basque, perhaps, or something Finno-Ugric—and the job of reproducing this strange dream argot is best left to the especially gifted or blighted, to those possessed of surpassing insight.

|

The Dream Songs, John Berryman’s epic two-book sequence of three-stanza poems about one Henry, a.k.a. Mr. Bones, is one of these rare literary artifacts of the far side of human consciousness. These poems, as they stretch into the hundreds, rehearsing Henry’s complexes and struggles and obsessions, both waking and sleeping, are among the most painful, funniest, most lacerating, most naked of contemporary poetry’s accomplishments. They make Life Studies, by Robert Lowell, to use one confessional example, seem quaintly charming. The Dream Songs, despite their provocations—and many are their provocations (their high-risk treatment of race, for example, justifiably fretted over)—are impossible to read without a barely suppressed tear, or a heave of nervous laughter. Who, for example, can look past the honesty of the celebrated #14: “Life, friends, is boring. We should not say so.” How to read #14 without nervous agitation and black humor in equal measure? (And, for the record, which “we” is it that we should understand to be narrating the second sentence above? The “we” of poetry itself, but also the multitude of Henrys, who are Legion?) What sequence of poems, prior to modernism, and mid-century, could be quite so annihilating about life, when celebrating life is more often held to be the poetic job? And yet the annihilation, with its consequent sympathies, is so moving!

The work’s historical intention seems to come from the decadents, perhaps—from voices like Huysmans or from Verlaine; or perhaps from the romantics, from Blake or Coleridge; in either case from some time past in which formal invention—e.g, the suppleness and playfulness of Berryman’s exploded sonnets and his irregular rhymes and ghost meters—is anything but sloppy and always acutely aware of literary precedent. The combination—of dream displacement and formal rigor—is illustrative of Berryman’s ambition. And yet, again, this is to understate the emotional wallop of the work.

Though the dream is contested literary terrain, it is the business of Berryman’s Henry to be inside of consciousness, where dreams are mass-produced, and so The Dream Songs are nothing without the full repast of human selves to be found in those oneiric realms. These are, then, the kinds of dreams that awaken you, for being too vivid, too real, too unsettling, even if pleasurable. They are the dreams recounted which do not lose a reader, rather they fix the reader to the page, where poetry is new again, and vital, and human, and genuine, and discomfiting, and inexhaustible.

Rick Moody is the author of, most recently, The Four Fingers of Death, a novel, and On Celestial Music: And Other Adventures in Listening, a work of nonfiction.

Photography by Bob Peterson. (©Bob Peterson)